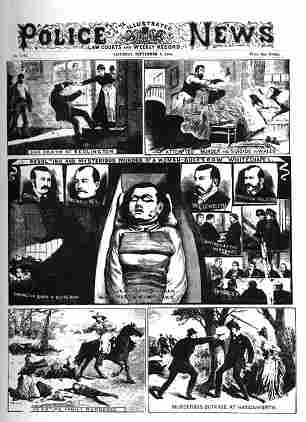

AT a quarter to four on Friday morning Police-constable Neil was on his beat in Buck's-row, Thomas-street, Whitechapel, when his attention was attracted to the body of a woman lying on the pavement close to the door of the stable-yard in connection with Essex Wharf. Buck's-row, like many other miser thoroughfares in this and similar neighbourhoods, is not overburdened with gas lamps, and in the dim light the constable at first thought that the woman had fallen down in a drunken stupor and was sleeping off the effects of a night's debauch. With the aid of the light from his bullseye lantern Neil at once perceived that the woman had been the victim of some horrible outrage. Her livid face was stained with blood and her throat cut from ear to ear. The constable at once alarmed the people living in the house next to the stable-yard, occupied by a carter named Green and his family, and also knocked up Mr. Walter Perkins, the resident manager of the Essex Wharf, on the opposite side of the road, which is very narrow at this point. Neither Mr. Perkins nor any of the Green family, although the latter were sleeping within a few yards of where the body was discovered, had heard any sound of a struggle. Dr. Llewellyn, who lives only a short distance away in Whitechapel-road, was at once sent for an promptly arrived on the scene. He found the body lying on its back across the gateway, and the briefest possible examination was sufficient to prove that life was extinct. Death had not long ensured, because the extremities were still warm. With the assistance of Police-sergeant Kirby and Police-constable Thane, the body was removed to the Whitechapel-road mortuary, and it was not until the unfortunate woman's clothes were removed that the horrible nature of the attack which had been made upon her transpired. It was then discovered that in addition to the gash in her throat, which had nearly severed the head from the body, the lower part of the abdomen had been ripped up, and the bowels were protruding. The abdominal wall, the whole length of the body, had been cut open, and on either side were two incised wounds almost as severe as the centre one. This reached from the lower part of the abdomen to the breast-bone. The instrument with which the wounds were inflicted must have been not only of the sharpness of a razor, but used with considerable ferocity. The murdered woman is about forty-five years of age, and 5ft. 2in. in height. She had a dark complexion, brown eyes, and brown hair, turning grey. At the time of her death she was wearing a brown ulster fastened with seven large metal buttons with the figure of a horse and a man standing by its side stamped thereon. She had a brown linsey frock and a grey woollen petticoat with a flannel underclothing, close-ribbed brown stays, black woollen stockings, side-spring boots, balck straw bonnet trimmed with black velvet. The mark "Lambeth Workhouse--P.R." was found stamped on the petticoat bands, and a hope is entertained that by this deceased's identity may be discovered. A photograph of the body has been taken, and this will be circulated amongst the workhouse officials.

On Saturday Mr. Wynne E. Baxter, the coroner for South-East Middlesex, opened an inquiry at the Working Lads' Institute, Whitechapel-road. Inspector Helston, who has the case in hand, attended, with other officers, on behalf of the Criminal Investigation Department. Edward Walker was the first witness called. He said: I live at 15, Maldwell-street, Albany-road, Camberwell, and have no occupation. I was a smith when I was at work, but I am not now. I have seen the body in the mortuary, and to the best of my belief it is my daughter, but I have not seen her for three years. I recognise her by her general appearance and by a little mark she had on her forehead when a child. She also has either one or two teeth out, the same as teh woman I have just seen. My daughter's name was Mary Ann Nicholls, and she had been married twenty-two years. Her husband's name was Williams Nicholls, and he is alive. He is a machinist. They have been living apart for some length of time, about seven or eight years. I last heard of her before Easter. She was forty-two years of age.--The Coroner: How did you see her? Witness: She wrote to me.--The Coroner: Is this letter in her handwriting? Witness: Yes, that is her writing.

The letter, which was dated April 17th, 1888, was read by the coroner, and referred to a place which the deceased had gone to at Wandsworth.

The Coroner: When did you last see her alive? Witness: Two years ago last June.--The Coroner: Was she then in a good situation? Witness: I don't know. I was not on speaking terms with her. She had been living with me three or four years previously, but thought she could better herself, so I let her go.--The Coroner: What did she doo after she left you? Witness: I don't know.--The Coroner: This letter seems to suggest that she was in a decent situation. Witness: She had only just gone there.--The Coroner: Was she a sober woman? Witness: Well, at time she drank, and that was why we did not agree.--The Coroner: Was she fast? Witness: No; I never heard anything of that sort. She used to go with some young women and men that she new, but I never heard of anything improper.--The Coroner: Have you any idea of what she has been doing lately? Witness: I have not the slightest idea.--The Coroner: She must have drank heavily for you to turn her out of doors? Witness: I never turned her out. She had no need to be like this while I had a home for her.--The Coroner: How is it that she and her husband were not living together? Witness: When she was confined her husband took on with the young woman who came to nurse her, and they parted, he living with the nurse, by whom he has another family.--The Coroner: Have you any reasonable doubt that this is your daughter.--Witness: No, I have not. I know nothing about her acquaintances, or what she had been doing for a living. I had no idea she was over here in this part of the town. She has had five children, the eldest being twenty-one years old and the youngest eight or nine years. One of them lives with me, and the other four are with their father. The Coroner: Has she ever lived with anybody since she left her husband?--Witness: I believe she was once stopping with a man in York-street, Walworth. His name was Drew, and he was a smith by trade. He is living there now, I believe. The parish of Lambeth summoned her husband for the keep of the children, but the summons was dismissed, as it was proved that she was then living with another man. I don't know who that man was.--The Coroner: Was she ever in the workhouse? Witness: Yes, sir; Lambeth Workhouse, in April last, and went from there to a situation in Wandsworth.--By the Jury: The husband resides at Coburg-road, Old Kent-road. I don't know if he knows of her death.--Coroner: Is there anything you know of likely to throw any light upon this affair? Witness: No; I don't think she had any enemies, she was too good for that.

John Neil, police-constable 97 J, said: On Friday morning I was preceeding down Buck's-row, Whitechapel, going towards Brady-street. There was not a soul about. I had been round there half an hour previously, and I saw no one then. I was on teh right hand side of the street when I noticed a figure lying in the street. It was dark at the time, though there was a street lamp shining at the end of the row. I went across and found deceased lying outside a gateway, her head towards the east. The gateway was closed. It was about nine or ten feet high, and led to some stables. There were houses from teh gateway eastward, and the School Board school occupies the westward. On the opposite side of the road is Essex Wharf. Deceased was lying lengthways along the street, her left hand touching the gate. I examined the body by the aid of my lantern, and noticed blood oozing from a wound in the throat. She was lying on her back, with her clothes disarranged. I felt her arm, which was quite warm, from the joints upwards. Her eyes were wide open. Her bonnet was off and lying at her side, close to the left hand. I heard a constable passing Brady-street, so I called him. I did not whistle. I said to him, "Run at once for Dr. Llewellyn," and seeing another constable in Baker's-row, I sent him for the ambulance. The doctor arrived in a very short time. I had, in the meantime, rung the bell at Essex Whard, and asked if any disturbance had been heard. The reply was "No." Sergeant Kirby came after and he knocked. The doctor looked at the woman and then said, "Move the woman to the mortuary. She is dead, and I will make a further examination of her." We then placed her on the ambulance, and moved her there. Inspector Spratley came to the mortuary, and while taking a description of the deceased turned up her clothes, and found that she was disembowelled. This had not been noticed by any of them before. On the body was found a piece of comb and a bit of looking-glass. No money was found, but an unmarked white handkerchief was found in her pocket.

The Coroner: Did you notice any blood where she was found? Witness: There was a pool of blood just where her neck was lying. The blood was then running from the wound in her neck.--The Coroner: Did you hear any noise that night? Witness: No; I heard nothing. The farthest I had been that night was just through the Whitechapel-road and up Baker's-row. I was never far away from the spot.--The Coroner: Whitechapel-road is busy in the early morning, I believe. Could anybody have escaped that way? Witness: Oh, yes, sir. I saw a number of women in the main road going home. At that time anyone could have got away.--The Coroner: Someone searched the ground, I believe? Witness: Yes; I examined it while the doctor was being sent for.--Inspector Spratley: I examined the road, sir, in daylight.--A Juryman (to witness): Did you see a trap in the road at all? Witness: No.

A Juryman: Knowing that the body was warm, did it not strike you that it might just have been laid there, and that the woman was killed elsewhere?" Witness: I examined the road, but did not see the mark of wheels. The first to arrive on the scene after I had discovered the body were two men who worked at a slaughter-house opposite. They said they knew nothing of the affair, and that they had not heard any screams. I had previously seen the men at work. That would be about a quarter-past three, or half an hour before I found the body.

Henry Llewellyn, surgeon, said: On Friday morning I was called to Buck's-row at about four o'clock. The constable told me what I was wanted for. On reaching Buck's-row I found the deceased woman lying flat on her back in the pathway, her legs extended. I found she was dead, and that she had severe injuries to her throat. Her hands and wrists were cold, but the body and lower extremities were warm. I examined her chest and felt the heart. It was dark at the time. I believe she had not been dead more than half an hour. I am quite certain that the injuries to her neck were not self-inflicted. There was very little blood round the neck. There were no marks of any struggle or of blood, as if the body had been dragged. I told the police to take her to the mortuary, and I would make another examination. About an hour later I was sent for by the inspector to see the injuries he had discovered on the body. I went, and saw that the abdomen was cut very extensively. I have this morning made a post-mortem examination of the body. I found it to be that of a female about forty or forty-five years. Five of the teeth are missing, and there is a slight laceration of the tongue. On the right side of the face there is a bruise running along the lower part of the jaw. It might have been caused by a blow with the fist or pressure by the thumb. On the left side of the face there was a circular bruise, which also might have been done by the pressure of the fingers. On the left side of the neck, about an inch below the jaw, there was an incision about four inches long and running from a point immediately below the ear. An inch below on the same side and commencing about an inch in front of it was a circular incision terminating at a point three inches below the right jaw. This incision completely severs all the tissues down to the vertabrae. The large vessels of the neck on both sides were severed. The incision is about eight inches long. These cuts must have been caused with a long-bladed knife, moderately sharp, and used with great violence. No blood at all was found on the breast, either of the body or clothes. There were no injuries about the body till just about the lower part of the abdomen. Two or three inches from the left side was a wound running in a jagged manner. It was a very deep wound, and the tissues were cut through. There were several incisions running across the abdomen. On the right side there were also three or four similar cuts running downwards. All these had been caused by a knife, which had been used violently and been used downwards. The injuries were from left to right, and might have been done by a left-handed person. All the injuries had been done by the same instrument. The inquiry was adjourned.

On Monday the inquest was resumed. Inspector John Spratling, of the J Division, was the first witness called. He stated that he first heard of the murder about half-past four on Friday morning, while in Hackney-road. Proceeded to Buck's-row, he saw Police-constable Thain there, and the constable pointed out the spot where the deceased had been found. Witness noticed a slight stain of blood on the footpath. Witness, continuing, stated that he returned to the mortuary about noon on Friday. He then found the body stripped, and the clothes lying in a heap in the yard. The clothes consisted of a reddish brown ulster, with seven large brass buttons. It was apparently an old garment, but a brown linsey dress looked new. There was a grey woollen petticoat and a flannel one belonging to the workhouse. Some pieces bearing the words "Lambeth Workhouse, P.R." (Prince's-road), had been cut out by inspector Helson with the object of identifying th edeceased. Among the clothes there was also a pair of stays in fairly good condition, though they had been repaired, but he did not notice how they fastened.

Henry Tompkins, of Coventry-street, Bethnal-green, stated that he was a horse slaughterer in the employ of Mr. Barber. He was at work in teh slaughterhouse, Winthrop street, adjoining Buck's-row, from eight o'clock on Thursday night till twenty minutes past four o'clock on Friday morning. He generally went home after leaving work, but that morning he had a walk. A police-constable passed the slaughterhouse about a quarter-past four, and told the men there that a woman had been murdered in Buck's-row. They then went to see the dead woman. Besides witness two other men, named James Mumford and Charles Britten, worked in the slaughterhouse. Witness and Britten had been out of the slaughterhouse previously that night, namely, from twenty minutes past twelve till one o'clock, but not afterwards till they went to see teh body. It was not a great distance from the slaughterhouse to the spot where the deceased was found. The work at the slaughterhouse was very quiet work.

The Coroner: Was all quiet, say after two o'clock on Friday morning? Witness: Yes, quite quiet. The gates were open, and we heard no cry.--The Coroner asked if anybody came to the slaughterhouse that morning. Witness stated that nobody passed except the policeman.--The Coroner: Were there any women about? Witness: Oh, I don't know anything about them. I don't like them. (Laughter.)--The Coroner: Never mind whether you like them or not. Were there any about that night? Witness replied that in Whitechapel-road there were all sorts and sizes. (Laughter.) He could tell them that it was a rough neighbourhood.--The Coroner: Had anybody called for assistance from the spot where the deceased was found would you have heard it in the slaughterhouse? Witness thought not, as it was too far away. When he arrived in Buck's-row with the intention of seeing the murdered woman he found the doctor and three or four policemen there, and he believed that two other men whom he did not know were also there. He heard no statement as to how the deceased came into Buck's-row. About a dozen people came up before the body was taken away. He did not see anyone from one o'clock on Friday morning till a quarter-past four, when the policeman passed the slaughterhouse.

A Juror: Did you hear any vehicle pass the slaughterhouse? No, sir. If one had passed I should have heard it.--Where did you go when you went out between twenty minutes past twelve and one o'clock? My mate and I went to the front of the road.--Is not your usual time of quitting work six in the morning? No; it is according to what we have to do.--Why did the constable call to tell you about the murder? He called to get his cape.

Detective-inspector Joseph Helson said that he received information about the discovery of the body at a quarter to seven o'clock on Friday morning, and between eight and nine o'clock he saw the body, with the clothing still on it, at the mortuary. He noticed that the dress was fastened in front with the exception of two or three buttons, and the stays were also fastened. They were fastened with clasps, and were fairly tight but short. There was blood in the hair and about the collars of the dress and ulster, but he saw none at the back of the skirts. He found no marks on the arms such as would indicate a struggle and no cuts in the clothing. All the wounds could, in my opinion, have been inflicted without the removal of the clothing. The only suspicious mark about the place where the body was found was one spot in Brady-street. It might have been blood.

A Juror: Did the body look as if it had been brought dead to Buck's-row? Witness: No, I should say that the offence was committed on the spot.

Police-constable Mizen deposed that at about a quarter to four o'clock on Friday morning, while he was at the corner of Hanbury-street and Baker's-row, a carman passing by, in company with another man, said, "You are wanted in Buck's-row by a policeman. A woman is lying there." The witness then went to Buck's-row, and Police-constable Neil sent him for the ambulance. Nobody but Neil was with the body at that time.--In reply to a juryman, witness said that when the carman spoke to him he was engaged in knocking people up, and he finished knocking at the one place where he was at the time, giving two or three knocks, and then went directly to Buck's-row, not wanting to knock up anyone else.

Charles A. Cross, a carman, said that he was in the employment of Messrs. Pickford and Co. He left home about half-past three o'clock on Friday morning to go to work, and in passing through Buck's-row he saw on the opposite side something lying against a gateway. He could not tell in the dark what it was at first. It looked like a tarpaulin sheet, but, stepping into the middle of the road, he saw that it was the body of a woman. At this time he heard a man--about forty yards off--approaching from the direction that witness had himself come from. He waited for the man, who started on one side, as if afraid that witness meant to knock him down. Witness said, "Come and look over here. There's a woman." They then went over to the body. Witness took hold of teh hands of the woman, and the other man stooped over her head to look at her. Feeling the hands cold and limp witness said, "I believe she's dead." Then he touched her face, which felt warm. The other man put his head on her heart saying, "I think she's breathing, but it is very little if she is." The man suggested that they should "shift her," meaning to set her upright. Witness answered, "I am not going to touch her." The other man tried to pull her clothes down to cover her legs, but they did not seem as if they would come down. Her bonnet was off, but close to her head. Witness did not notice that her throat was cut. The night was very dark. Witness and the other man left the woman, and in Baker's-row they saw Police-constable Mizen. They told him that a woman was lying in Buck's-row, witness adding, "She looks to me to be either dead or drunk." The other man observed, "I think she's dead." The policeman replied, "All right." The other man, who appeared to be a carman, left witness soon afterwards. Witness did not see Constable Neil. He saw no one except the man that overtook him, the constable in Baker's-row whom he spoke to, and the deceased. In reply to further questions, the witness said the deceased looked to him at the time as if she had been outraged, and had gone off in a swoon. He had then no idea that she was so seriously injured. The other man merely said that he would have fetched a policeman, but he was behind time. Witness was behind time himself. He did not tell constable Mizen that another policeman wanted him in Buck's-row.

William Nicholls, a printer's machinist, living in Coburg-road, Old Kent-road, said that the deceased woman was his wife. They did not live together, but had lived apart for eight years last Easter. He last saw her alive about three years ago. He had not heard from her since. He did not know what she had been doing during the last three years.--A Juror: It is said that you were summoned by the Lambeth Union for her maintenance, and that you pleaded that she was living with another man. Did that refer to the blacksmith that she had lived with? Witness: No, to another man or men. I had her watched. That was seven years ago. The Juror: Did you leave her or did she leave you? Witness: She left me. She had no occasion for leaving me.--The witness further stated that but for the drink his wife would have been all right. It was not true that he took up with a nurse eight years ago when his wife left him.

Emily Holland stated that she was a married woman, and lived at Thrawl-street, Spitalfields, in a common lodging-house. Deceased had lived there about six weeks, but was not there during the last ten days. AT about half-past two o'clock on Friday morning witness saw the deceased going down Osborne-street into Whitechapel-road. She was staggering along drunk and was alone. She told witness that where she had been living recently they would not let her in because she could not pay. Witness tried to persuade her to go home with her. The deceased refused, saying, "I have had my lodging-money three times to-day, and have spent it." The deceased then went along Whitechapel-road, stating that she was going to get some money to pay for her lodgings. Witness did not know what deceased did for a living, or whether she stayed out late at night. She was a quiet woman, and kept herself to herself. Witness did not know whether she had any male acquaintance or not. She had never seen the deceased quarrel with anybody. When deceased left witness at the corner of Osborne-street and Whitechapel-road she said that she would not be long before she was back.

Mary Ann Monk deposed that she last saw the deceased about seven weeks ago in a public-house in New Kent-road. She had previously seen her in the Lambeth Workhouse, but she had no knowledge of the acquaintance of the deceased.

As this was all the evidence the police were prepared to offer at present, the inquest was then adjourned until the 17th inst., and it was arranged that the jury should inspect the clothes of the deceased at the mortuary instead of in the room where the inquiry was held.

Notwithstanding every effort the police engaged in investigating the murder of Mary Ann Nicholls have to confess themselves baffled, their numerous inquiries having yielded no positive clue to the perpetrator of the crime. At the conclusion of the inquest Detective-inspector Abberline and Detective-inspector Helson were busily engaged in the matter, but have not elicited any new facts of importance. A large number of constables are engaged upon the case. Crowds of spectators continue to visit the scene of the murder in Buck's-row.