On 16 May 1963, London celebrated the centenary of the birth of its underground railway system. A gathering of invited transport officials from various parts of the world was shown the modern Underground system at work and in contrast, part of its history in review. The spectacle included a replica of the very earliest train complete with passengers in the period dress, and a parade of steam and electric rolling stock spanning 100 years of operation. This was the beginning, the culmination of ideas born earlier, when someone thought of trains that would start in London's suburbs, and then plunge beneath the City's buildings and streets to disgorge passengers in its very centre - or even take them under London to the other side. At about this time a trip to the moon by aerial machine was also being considered, but the overriding opinion of city gentlemen was that neither idea was worth a second thought. It is difficult for us to imagine the scepticism of people in those far-off days. They ridiculed the scheme -- not only the uneducated, but also some we would regard as clear-thinking and level-headed. Perhaps their attitude was not unreasonable, for only 20 years before the Underground idea was broached, London had no railway at all. In 1836 the first line began to work between Spa Road and Deptford, and it is probable that 20 years later many Londoners had never even travelled on a train. They walked, or went on horseback or took hackney carriages, whose speed was not much more than six miles an hour. It is estimated that by 1850 over 750,000 people entered London every day, either by main line railways or by road, and the streets were becoming blocked. A plan was eventually evolved for an underground, steam-operated railway nearly four miles long between Farringdon Street and Bishop's Road, Paddington, following Farringdon Road and King's Cross Road to King's Cross, and then following the course of Euston Road, Marylebone Road and Praed Street to Paddington. Thus it would serve as a link between three main-line railway terminii - the Great Western at Paddington, the London & North Western at Euston, and the Great Northern at King's Cross. Farringdon Street was chosen as a site for the eastern terminus principally because the City Cattle Market, then occupying the site, was about to be moved to the Caledonian Road at Islington. The constructional work began in 1860, and within 2-and-a-half years it was completed -- a remarkable achievement considering the amount of work involved in diverting sewers and gas and water mains, with very little in the way of previous experience to guide the constructors.

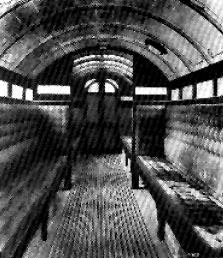

The Metropolitan Railway, as it became known, was built on the 'cut and cover' method. Where it was to run under streets a huge trench was dug, lined with brickwork and roofed over, and the streets relaid for surface traffic. Although this method made chasms of certain streets and must have paralysed traffic in their immediate vicinity, it made possible the construction of the line without interfering to any great extent to private property. Some idea of the amount of earth excavated for that early railway can be gathered by those who know the Chelsea football ground at Stamford Bridge. The terraces there was raised from that soil. The job of constructing such a railway would be deemed an intricate one even today; but it was done successfully, for the original massive brickwork is still in good condition. The only real setback occurred when the Fleet Ditch Sewer burst and flooded the workings to a depth of 10ft as far as King's Cross, but even this proved only a temporary setback. Mr. and Mrs. Gladstone and other notables rode through the echoing tunnels on Private View Day in open trucks (see above right). Then, to celebrate the opening of the railway on 10 January 1863, many hundreds of people were invited to attend a great banquet at Farringdon Street Station - and the trains, as they approached the station, were heralded by music from a band! The public rode in closed carriages -- only on the first trial trips were open trucks used.

It was foreseen at the outset that the Metropolitan would eventually connect with other railway systems, and subsequently this occurred; the Great Western operated a service from Windsor to Farringdon Street via a junction at Paddington; the Midland, Great Northern and Great Eastern Railways connected through underground junctions at King's Cross and Liverpool Street respectively, and the London, Chatham & Dover Railway was linked at Farringdon Street by a short connecting line from Blackfriars.

9,500,000 Londoners were carried in the first year, 12,000,000 the second, and each year after that more and more. Its popularity was further enhanced by the addition of two trains exclusively for workmen. One ran to the City in the morning and the other ran out of the City in the evening, carrying workmen for a fare of one penny for each single journey. The first section of the District Railway was opened in late 1868 between South Kensington and Westminster, a distance of just over two miles. For its first 2-and-a-half years it was worked by Metropolitan stock, under an agreement between the two companies, but in the meantime it had extended its lines eastward under Victoria Embankment to Blackfriars. In the east the Metropolitan had been busy tunnelling towards Aldgate. The purpose of these short and enormously expensive City extensions was eventually to link the Metropolitan with the District, and so form the Inner Circle line, over which both railways intended to run services to their mutual benefit. To effect this most important link each company agreed to build part of the connecting line. Its length was just 1 mile 10 chains, connecting at a junction with the District at Mansion House, running due east to Mark Lane and finally curving north to make a junction with the Metropolitan at Aldgate Station. By its completion in 1884 an Inner Circle line, already made continuous in the west by a junction at South Kensington, became reality. This became the Circle Line. The Twin Lines system also connected in that year with the East London Railway, 4-and-a-half miles extending from Shoreditch to New Cross, where it forked to serve respectively the South Eastern and the London, Brighton & South Coast stations. This new link enabled through trains to be run between Hammersmith and New Cross via a spur tunnel at Whitechapel (opened 6 October 1884) and the Thames Tunnel. The steam locomotives of both the Metropolitan and the District railways were expressions of a single design -- the 4-4-0Ts built by Beyer, Peacock & Company. All the locomotives built from 1871 (44 in all) were still in 1905 when electrification was accomplished. Their olive green colour combined with polished brass dome covers gave the locomotives a smart appearance even though they operated in smoke-filled tunnels. In one particular they were different for the period, in that they were fitted with condensing gear, which gave the driver a means of diverting exhaust steam from the chimney outlet into the water tanks, where the exhaust condensed, leaving the tunnels more or less clear of smoke and vapour. The original passenger coaches were divided into first, second and third class compartments, the first being fitted with carpets, mirrors and well-upholstered seats. Furnishings decreased in elegance according to the class, as did the space allotted per person, and we can imagine that the third-class passenger was glad to resurface, stiff after a ride during which all the windows had to be kept closed.

One of the biggest problems confronting the engineers of the underground steam railways was to provide and maintain a supply of breathable air in tunnels and stations. The Metropolitan engines burned coke, which is clean but gives off poisonous fumes, and after abortive trials with additional ventilators at the stations, the railway went over to coal, with the immediate result of an extremely smoky atmosphere. As a remedy, certain openings originally provided in the covered way at King's Cross and elsewhere for lighting purposes were adapted as smoke vents, and finally 'blow holes' were bored all along the route between King's Cross and Edgware Road. They were covered by gratings in the roadways above, and were prone to sudden belching of steamy vapour which startled the passing horses. So much about the Metropolitan and District lines were trial and error that it is not surprising that their fortunes should fluctuate -- the District Railway in particular had many lean years, but its prospects were brightened by events that its promoters could hardly have foreseen. These were the exhibitions held annually at South Kensington, and followed by the famous exhibitions at Earls Court. The great American and Buffalo Bill show there in 1887 was immensely popular, and the District Railway took full advantage of these displays and issued combined rail and entry tickets. The electrification of the Metropolitan and District systems in 1905 was easily the most important event in their respective lives. It was almost a case of electrification or die, for as steam lines their position was deteriorating rapidly in the face of competition from the recently-opened tube railways. Electrification was necessarily a joint undertaking since Inner Circle Metropolitan trains ran over part of the District territory, and in any case their interests had too much in common to allow one railway to electrify with the other.

Eventually the two lines decided to electrify the up and down sections of line between Earls Court and High Street Kensington, as an experiment. This was in 1899, and in the following year a six-coach train comprising two motor coaches and four trailers was tested against a steam-hauled train. The electric train came out of the test with flying colours, and was run on this section of line as a passenger train, the fare being one shilling, against 2d to 4d on the steam. Although by this time both companies had decided to go ahead with electrification, it was not to be a straightforward matter of getting the job done quickly, for a dispute arose between the two companies as to the particular electrical system to be adopted. The Metropolitan favoured the Ganz system of high-tension alternating current, which was to be generated at 11-12,000V and stepped down by static transformers to 3,000V, at which pressure it was to be transferred to overhead copper wire conductors. The Metropolitan's advisers maintained that this system would prove most economical, since it would require no substations and no heavy conductor rail such as would be necessary with a system using low-tension direct current. Another advantage they claimed was that the static transformers required no attendants and could be locked in a room and left to work themselves. The District, on the other hand, favoured the British Thomson-Houston Company's low-tension system by which direct current was to be fed to conductor rails on the track. The matter was complicated by the fact that the Metropolitan was then financially sound and therefore powerful enough to insist, if necessary, on its own favoured electrical system; the District on the other hand was practically bankrupt but sincerely believed in the superiority of its system. At this stag there appeared on the scene Charles Tyson Yerkes, an American who for ten years had financed the equipping of elevated railroads and electric tramways in America. The controlling group of shareholders of the District Railway stock had turned to him for financial help, and their negotiations resulted in the formation of the Metropolitan District Electric Traction Co. Ltd, a move which improved the District's financial position and gave it equal bargaining powers with the Metropolitan Railway. Yerkes refused to act on the expert advice which favoured the Metropolitan system, and even went so far as to visit Budapest to see the Ganz system, which had been applied to a short section of railway there. He did not see it because by this time the experimental section of line had been dismantled, but he did see the 67-mile Valtellina line, which ran from Lecco alongside Lake Como to Sondrio, and whether he was influenced or not as a result, he finally decided that overhead conductors would not suit London systems. The matter was now a really serious issue between the two companies, and they finally went to arbitration -- the Press making a great play of the controversy meanwhile. After a long sitting the tribunal appointed by the Board of Trade gave judgement for the D.C. system, and the tremendous jobs of building great power stations at Lots Road and Neasden and many substations, and laying miles of cable, were at last put in hand. Some 26 miles in all of the Metropolitan were electrified in three years, a very creditable performance considering the line was clear for workmen for only about six hours out of every 24. The length of the District to be electrified was even more. At first an experimental electrified line between Ealing and South Harrow was laid down and used both for testing the installation and for training crews to operate the new electric trains. While this was going on the work of electrification was proceeding steadily, and eventually on 22 September 1905 the last steam train puffed around the Inner Circle. Not many months after its exit the whole programme of electrification of both railways was completed. Long, well-lit saloon coaches for passengers replaced the discomforts of dim and stuffy compartment coaches. It was as if the authorities wished to wipe the memories of steam trains from the minds of their passengers, for stations and tunnels were thoroughly cleaned of accumulated layers of soot and grime, and there was much repainting of both lines as soon as possible afterwards. The two companies were eager to make their railways more attractive than those of the competitive tube lines.

Opening dates of sections of line until 1900:

Underground services operated Whitechapel to New Cross and New Cross Gate.

Source: "London's Underground" by H. F. Howson