|

|

|

|

|

|

| Author |

Message |

Chris Scott

Assistant Commissioner

Username: Chris

Post Number: 1479

Registered: 4-2003

| | Posted on Sunday, October 31, 2004 - 11:25 am: |

|

I have recently obtained 3 bound volumes of an 1880's magazine called The Quiver. I have the yearly issues for 1883, 84 and 87. There are a number of articles which will, I hope, be of interest for background information.

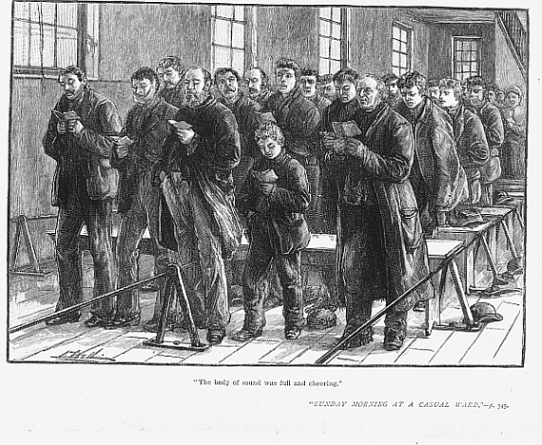

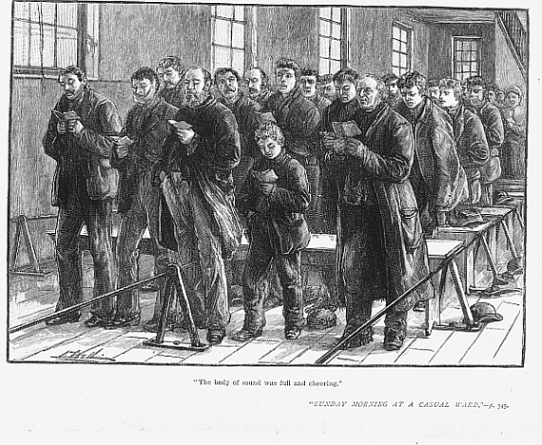

The first one which I will be transcribing is entitled "Sunday Morning at a Casual Ward" and describes the scene at the Casual Ward at the Whitechapel Infirmary at Baker's Row. It is by the Rev. A.E. Buckland and comes from the 1883 issue. It has one illustration which I am attaching. Other articles I have found so far include:

East End Rescue Workers

A Night with the Wapping Police

East End Photographers

I will posting these as soon as they are done

Chris

(Message edited by Chris on October 31, 2004) |

Christopher T George

Assistant Commissioner

Username: Chrisg

Post Number: 1013

Registered: 2-2003

| | Posted on Monday, November 01, 2004 - 9:29 am: |

|

Hi Chris

As usual, any articles that illuminate our knowledge of the East End and the social conditions in the areas in which the Whitechapel murders took place will prove of great value to those of us researching the crimes. Thanks once more, Chris, for your obtaining these articles and posting the information and illustrations. It is much appreciated.

All my best

Chris

Christopher T. George

North American Editor

Ripperologist

http://www.ripperologist.info

|

Chris Scott

Assistant Commissioner

Username: Chris

Post Number: 1481

Registered: 4-2003

| | Posted on Tuesday, November 02, 2004 - 9:43 am: |

|

Articles from "The Quiver"

1883 Edition

SUNDAY MORNING AT A CASUAL WARD

BY THE REV. A.R. BUCKLAND B.A.

The Whitechapel Road on Saturday night exhibits a scene of turmoil and confusion in many ways peculiar to itself. The bustling crowd has its own strongly marked characteristics - a sprinkling of mariners from many lands; multitudes of Jews discoursing in diverse tongues; bewigged Jewesses, some brave with many coloured apparel, others dirty as the street boys trotting in and out amongst them; honest men and their wives "marketing;" other men and women, palpably dishonest, rarely quite sober, rough in manner, and loud of speech. On every side there is noise and confusion; little else than evil sights and evil sounds. The Whitechapel Road on Sunday morning is by comparison another place. The bustling crowd is gone, represented now by only an occasional pedestrian; the shops are for the most part closed, and the flaring gas extinguished; the very air blowing down the street seems fresher than on weekday mornings. By ten o'clock the number of wayfarers has increased, and Whitechapel appears to be waking up. But still the almost unbroken array of closed shutters, and the comparative absence of traffic, suggests a Sabbath like rest from ordinary labours.

Baker's Row is a by street leading from the Whitechapel Road, a thoroughfare neither better nor worse than its neighbours. Amongst its own offshoots is a small street, a mere cul de sac, nestling beneath the tall buildings of Whitechapel Infirmary. Nearly at its far end appears a doorstep, wider and whiter than its fellows. An official looking bell hangs conspicuously by its side, and above the doorway appear the words "CASUAL WARD."

One pull at the formidable bell on a cold January morning brought to the door an aged pauper with the listless look peculiar to his class. The Superintendent's office, whither his shuffling steps conducted "the minister," was of very circumscribed area. No more than two or three visitors could at any time have been accommodated therein, and then the apartment would have been uncomfortably crowded. There on the desk behind the little window lay the slate on which the casuals' names are first entered, with the Union to which they belong. Side by side was the huge ledger like volume, into which these details are subsequently copied. A small line of loaves, flanked on one side by a Dutch cheese, and on the other by a cutting knife, suggested the scanty preparations for the casuals' midday meal.

Preceded by the Superintendent we entered the men's ward, bow prepared in a rough and ready way for divine service. Down the entire length of the room stretched the four lines of iron rails to which, raised but a foot from the ground, their single beds are attached at night. These had now been all unstrapped and formed a symmetrical stack, of small compass, in a distant corner. The wooden floor had been scrubbed until it approached that ideal state of cleanliness indicated by the possibility of eating one's dinner therefrom. Now there stretched from side to side forms of equal whiteness, and a small desk of obtrusively new deal, and the very simplest construction, awaited the speaker.

"Shall I send them up, sir?" asked the Superintendent.

"Yes, if everything is ready," was the answer. And then the inmates - confined for the day under the operation of the new law affecting casuals - came trooping in.

Some half dozen women led that way, headed by a worn and faded figure, suggestive of long and varied experience in such places. Behind her came a young girl, whose ragged and dirty clothing hung loosely from her attenuated frame. Her boots were many sizes too large, and clattered loudly upon the boards as she walked. Her face was clean, thanks to the compulsory bath; but what miserable experiences of hardship and sin were suggested by the cunning eyes and prematurely aged expression of the features! Two or three older woman, hugging ragged shawls to their breasts, closed the procession of female casuals.

Then came the men, and ranged themselves in comparative silence upon the wooden benches. They fumbled at their hymn books with the clumsiness of persons to whom the occupation was unusual, casting the while critical glances at the speaker. Whilst they were settling themselves for the service, one had an excellent opportunity of observing their faces and rags.

On the extreme right of the first form sat a casual who, if neatly dressed and trimmed by the hairdresser, would have struck any observer as a man of education and intelligence. Never once, whilst coming in or going out, did he lift his eyes from his book or the floor. But the head was massive and well formed; the broad sweep of the white brow was overhung by masses of shining black hair; a long and much neglected beard nearly hid the absence, which a side view made sufficiently apparent, of any shirt or collar. His dress was a black frock coat of fashionable cut, but now greasy with long wear, torn in several places, lacking an occasional button, and bursting at one of its seams. Beneath it appeared a pair of black trousers, frayed at the edges, and splashed thickly with mud, like the garments of one who had tramped many weary miles.

The immediate neighbour of this strange casual was one of those figures so familiar in London suburbs, or in towns where a generous display of rags and dirt is a sure passport to largess in money or kind. The man's uncut hair hung in lank grey locks upon a pair of round shoulders and the flowing beard would not have disgraced a Jewish Rabbi. His coat was a garment of singular shape and nature. Its original material was now doubtful, owing to the number and extent of the patches it bore; buttons had been dispensed with, probably as being articles beyond the wearer's scanty resources, and some four or five loops of stout twine brought the garment together across the chest. The boots he wore were in thorough harmony with the rest of his outfit. They were obviously not a pair, but rather suggested the idea that the owner had found or been presented with one superior boot, and had thereupon cast away one of the original pair in its favour. The right foot was well covered, and looked equal to the exclusion of rain and mud, but its fellow was an old traveller, a large boot, designedly cut in more then one place, and falling to pieces from sheer decay in others - a dilapidated shell from which the wearer's toes were obtrusively sprouting.

There were many other men amongst the company whose appearances suggested melancholy reflections. How came that burly, florid labourer to be seated amongst those professional tramps? His was not the counterfeit air of your town vagabond who assumes the role of a distressed agriculturalist for his own business purposes. There was no mistaking the genuine character of his dress and looks. Had he left a wife and children in the country, and walked up to London, as so many do, in expectation that nobody willing to work could fail there to find a job? Had he, after applying for work in all directions, found every avenue of the labour market crowded with applicants as needy, but as willing as himself, and then - his carefully husbanded resources at last gone - had the pangs of hunger driven him to the Casual Ward? Possibly so; such cases are of everyday occurrence. The idea that in London any man can find work, if he is willing, is one based on imagination rather than fact. It is, unhappily, an idea which brings hundreds of men to London, many of whom rapidly lose heart and join the ranks of paupers or criminals. The blame of this is often laid upon clergy and magistrates in the country. But the charge may possibly be false.

Just under one window sat a young man, little more than a lad, dressed in a faded tweed suit, and with a look of blank despair on his face. Was his the old story of some rash misdeed whereby a good name had been lost, and a family brought to shame? Just such a young man I had seen taken from this ward two years before, and sent to sea; only to learn some months later that his ship had been wrecked, and his life lost upon the first voyage. Nearly every common lodging house in London has among its occupants lads and young men, sometimes of good birth and education, whose stories are practically identical.

The main body of the casuals consisted of the professional element - men who were vagrants by inclination, whose acquaintance with this and other wards was probably co-extensive with their experience of London and provincial gaols. Behind the speaker's desk sat the Superintendent and his neatly dressed wife, representatives of the world of uprightness and good repute from which their prisoners had fallen.

Whilst we had been looking up and down their ranks the congregation had laboriously found the first hymn, a few of the more uneducated receiving assistance from their neighbours. Then we all stood up and passers by might have heard from within the gloomy ward the sound of "Come, let us join our cheerful songs." As far as the singing went there was no mockery in that opening line. Perhaps they sang as a welcome relaxation; at all events, the body of sound was full and cheering, and even the unmusical amongst them growled out some inharmonious setting of the words.

After this hymn, and a word or two of application suggested by some of its lines, we commended ourselves and the meeting to God. During the prayer we heard no noise from the congregation. There may have been open eyes and wandering thoughts, but, after all, such things are not exclusively confined to Casual Ward services.

After the prayer came another hymn, and then a passage of Scripture was read and commented upon at length in language suited to their comprehension. They listened, did these men and women of poverty and sin, with perhaps more than the attention of an ordinary congregation. There was no studied attitude of devotion, no conventional air of propriety; but yet no sign of abstracted attention. Their look was that of persons who were willing to believe the tidings to be of extreme importance to themselves, but still despaired of any practical application of these truths in their own case. After the habitual indifference to such subjects has been overcome with these hearers, there yet remains in their hearts an utter hopelessness of any change being possible in their own lives. It was when one handled facts, and spoke of men one had known who had been raised form similar depths of sin to their own, that their interest grew deeper, and a ray of hope seemed to shine forth into some hearts. The address or sermon over, we sang together the familiar hymn, "There is a Fountain filled with blood." The singing was even more general this time, but my hearer in the front row - he of the broad brow and air of a lost position - still stood with bent head and firmly closed lips.

After a few words of comment upon the hymn, and another short prayer, our meeting came to an end. Then one by one the casuals filed out, casting hungry glances into the little office, where the aged pauper in worn corduroy was slicing up the yellow Dutch cheese for their approaching dinner. In another room, and almost in semi darkness, they passed the rest of the day, talking over past exploits or future plans, telling or listening to childish stories eagerly called for, listlessly turning the leaves of some periodicals supplied for their use, or laboriously spelling out their contents. In the evening came a supper of dry bread - their only meal since the bread and cheese dinner - and then bed time. With the next day's light came more labour, than an end of their toil, and freedom again - liberty to pursue their chequered paths and accept or reject the Gospel message heard that day in the Casual Ward.

|

Robert Charles Linford

Assistant Commissioner

Username: Robert

Post Number: 3354

Registered: 3-2003

| | Posted on Tuesday, November 02, 2004 - 4:02 pm: |

|

Thanks for that, Chris. I have a piece by Rev Buckland in a library book I have out. It's about the Church in London, and includes a photo of an open air service, St Mary Whitechapel...in Yiddish!

Robert |

denise stevens

Unregistered guest

| | Posted on Monday, March 21, 2005 - 3:26 pm: |

|

I was shocked to find a great aunt was in the Bakers Row infirmary listed as a pauper inmate in the 1891 Census. I am trying to find out more about the conditions there and if possible when she died. Apparently she had already had a son in 1889 who was adopted by the family as their youngest son, but when she fell pregnant again she was obviously thrown out of the house. |

|

Use of these

message boards implies agreement and consent to our Terms of Use.

The views expressed here in no way reflect the views of the owners and

operators of Casebook: Jack the Ripper.

Our old message board content (45,000+ messages) is no longer available online, but a complete archive

is available on the Casebook At Home Edition, for 19.99 (US) plus shipping.

The "At Home" Edition works just like the real web site, but with absolutely no advertisements.

You can browse it anywhere - in the car, on the plane, on your front porch - without ever needing to hook up to

an internet connection. Click here to buy the Casebook At Home Edition.

|

|

|

|