|

|

|

|

|

|

| Author |

Message |

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 749

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Friday, July 29, 2005 - 9:27 pm: |

|

Gang...

I have a question that perhaps someone with knowledge of the procedures regarding hospital security can answer.

Is there a text or source, not produced or published by, for the sake of an example, London Hospital or any other metropolitan London hospital that exists that touches on how security was generally handled in or around 1888 ?

The reason that I emphasized the "not produced or published by" is thus...

If one requests a company brochure from, say, Ford Motors, it will only be a fluff piece, guaranteeing that everyone has a great on-the-job attitude, the management and workers play croquet on Lake Michigan together and all is kosher.

London Hospital, used as an example here only and not as an affront to the establishment, can't be expected to allow themselves to be seen as occasionally lax in security. They follow in the same mold as Ford or any company regarding their image.

However,is there,to your knowledge, a reference to the practices of hospitals from peripheral sources ?

Basically what I am driving at here is relative to Stephenson's necessity of leaving the Hospital during the evenings of the murders of the C5 and how it could have been pulled off...

I'm one of those who don't think that it was that hard to leave [ earlier in the evening,naturally ], but think that it would have been a little more difficult for RDS or anyone else,other than a doctor-in-residence, nurse, or security personnel, to enter,or in RDS' case, re-enter at the time of day that he would have had to.

Lets be frank. Its pretty hard to visualize RDS leaving on the four dates that the C5 murders occurred and re-entering London Hospital to his private ward,and being seen by Hospital personnel without arousing suspicion. This is perhaps as risky,if not more so,than the actual murders.....Risky in that Stephenson could very well have been conspicuous had he been seen re-entering by appearing "up" to something.....

Again,I don't see the leaving the Hospital as much of a problem as much as the re-entering. It presents a plethora of possible problems for RDS,since he knew the conditions upon leaving,but could not have,upon the return. He would have had no way of knowing if someone came to inquire on how he was doing or any other possible inquiries, while he was out and about. That and a few other possible scenarios,which we can leave for later...

Any ideas folks ?

(Message edited by howard on July 29, 2005) |

Sir Robert Anderson

Inspector

Username: Sirrobert

Post Number: 488

Registered: 2-2003

| | Posted on Friday, July 29, 2005 - 10:02 pm: |

|

",I don't see the leaving the Hospital as much of a problem as much as the re-entering ."

Especially as he'd be re-entering in the wee hours.... Leaving in the midst of a crowd is one thing; facing the graveyard shift (no pun intended) is another.

Sir Robert

'Tempus Omnia Revelat'

SirRobertAnderson@gmail.com

|

Harry Mann

Detective Sergeant

Username: Harry

Post Number: 128

Registered: 1-2005

| | Posted on Saturday, July 30, 2005 - 4:58 am: |

|

Howard,

It is possible to leave or reenter almost any establishment without being seen,depending somewhat on the connection with that place.

My first experience of a hospital stay was the early 1930's,and according to grandparents,little had changed since the late 1800's.

As a patient, there would of course be the times of medication to consider.Shift changes,always preceeded by a check of patients,both by oncoming and departing shifts.The inspections by supervisors,at intervals,both day and night.

That are some of the problems to overcome,so it would be extremely difficult for a patient to go missing for any considerable length of time.After all it may have taken the Ripper the best part of the night,in some instances,before a victim and circumstances permitted an opportunity to kill. |

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 750

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Saturday, July 30, 2005 - 8:06 am: |

|

Sir Bob:

Even today in 2005,with the security "atmosphere" at other places that the general public meet,such as airports,train stations,amusement parks and hotels,at an all time high for obvious reasons, the hospital is still an easy nut to crack. But the "graveyard" shift could have been a major problem as you infer.

When my Mom died in '96, I went to see her for almost two months without once being queried,as soon as I had the initial meeting with the doctor who treated her on the first day, when I went to the hospital for the balance of the two months.

In fact, I could have put on a white coat,grabbed a clip board,and started practicing OBGYN at will. This hospital was considered an above average hospital,regarding quality of treatment to its patients [ which it was ] and in regard to security [ cameras all over the place ].

Yet..all it required to get to the two different rooms on two different floors during the 58 day stay was an ability to walk and get on an elevator. No problem at all....But,this was all done during the day,when people are less likely to pay attention to someone else's actions. The night is different. There is a different ambience in not just this issue,but in almost everything when it is done at night.

***********************************************

Dear Mr. Mann:

Do you believe that it could be managed, the departing from a hospital with average security back in the LVP for say, an hour,if there was no medication schedule..no inspectors or nurses "checking" on the patients...in a private ward?

Stephenson resided in the Davis Ward,which was a private ward. He signed in to the London Hospital in late July on the 26th. July 26th being a Thursday, just to make mention of that.

Putting RDS in the shoes of the Ripper for a moment here,Harry...Nichols is killed on a Friday,the 31st of August, early in the morning. Chapman is killed on a Saturday, early in the morning, on Sept. 8th.

Stride and Eddowes [ assuming that it was a double event for a moment ] on a Sunday morning, the 30th of September. Kelly on a Friday morning [ November 9th ].

So as we can see above, the period from a Friday night [ Nichols ] through a Sunday morning [ Stride/Eddowes ] would be the time frame of security in question.

Harry...would security on the weekends be comprised of a different cadre of security people and could it be a little more lax than it already appears to have been? |

Jeffrey Bloomfied

Chief Inspector

Username: Mayerling

Post Number: 770

Registered: 2-2003

| | Posted on Saturday, July 30, 2005 - 5:14 pm: |

|

Hi Howard,

Fascinating question, but the issue is simplified if you keep one thing in mind.

Let's say "Sudden Death" is JTR. Nobody on the staff (theoretically) knows this - he has not confided in the staff. He just needs the location of the hospital (which he checked himself into) as a base for operations that the authorities won's suspect (or won't suspect immediately). So whatever is the security of the hospital staff is something that D'Onston just has to work around: that is, they are not setting up security in the hospital to find Jack the Ripper. The security is set up for purposes like seeing if the patients are doing well, or in distress. There may be security for the purpose of protecting hospital property (machinery, supplies, drugs). There may be security dealing with those mental patients who the staff know are potentially dangerous to others. This would not (necessarily) include D'Onston, who is in for neuroesthenia (I think that's the spelling). If he was brought in by the police for killing somebody while in an epileptic fit, the security would be watching him carefully.

Perhaps after the butchery of Mary Kelly the hospitals took a different view of some of the patients because of the extent of savage mutilations in that case - then D'Onston would have more difficulties leaving the hospital without any note or question.

Best wishes,

Jeff |

Glenn G. Lauritz Andersson

Assistant Commissioner

Username: Glenna

Post Number: 3829

Registered: 8-2003

| | Posted on Saturday, July 30, 2005 - 7:15 pm: |

|

But Jeffrey,

Think about it for a minute.

If we assume that the killer may have had some blood-stains on his cuffs and maybe on his hands -- wouldn't it be rather dangerous and risky to take the chance and hope that the staff would notice him come and go at this time of night/morning?

After all, the Whitechapel murders were hot news in the papers and most people knew some of the details regarding the murders -- and if Black Death showed up at these hours at the hospital and maybe with blood on his hands or parts of his shirt or cuffs, wouldn't they be putting two and two together?

Sure if he WAS the killer, they obviously didn't spot him, but they could have. Put yourself in the killer's frame of mind here.

And what did he do with the organs/trophees? And with the clothes? After all, if he did carry some of the organs with him, they would be stained to some degree. The whole point with taking organs is to keep them close so that he can enjoy them. And I do think the doctors would notice if any items had been added to their own medical 'archive'. Just my views, though.

I admit I am not that well familiar with how hospitals works in England, and especially not how they worked in the 10th century, but still... this is a bit hard to swallow for me. Just too many obstacles.

All the best

G. Andersson, writer/crime historian

Sweden

The Swedes are the men That Will not be Blamed for Nothing

|

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 753

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Saturday, July 30, 2005 - 9:59 pm: |

|

Hey Glenn!

"If we assume that the killer may have had some blood-stains on his cuffs and maybe on his hands.."

Stephenson wouldn't have entered the Hospital with a big sign on his neck saying, "Hey..Its Me ! JTR !!"...neither would he have entered the Hospital with bloody hands or clothes. No offense to anyone,but think how that looks for just a second here...

"And what did he do with the organs/trophees? And with the clothes?"

Thats a better question. The additional clothes probably weren't needed.

One thing to consider, as we all assume here for a moment that it was RDS.., is that Stephenson more than likely would have taken a rag,towel,garment for cleaning up after the murders from the Hospital which wouldn't miss one being taken. The very fact that he took the piece of apron from Eddowes and not from Chapman or Nichols, may be...may be..because the cleaning rag he had taken prior to killing Stride was soiled or dropped.

"After all, if he did carry some of the organs with him, they would be stained to some degree.."

Yes sir..a major problem without a bolthole or storage place. Inevitably,without some sort of leakproof or near-leakproof container, the chance of a leak increased..

Because there is more risk involved taking the small [ we aren't talking about carrying a watermelon through the streets of London here..] organs and being potentially stopped on the streets, a bolthole idea seems logical from the position of the Ripper killing and then staying in that bolthole. There are just so many possible things that could go wrong in this extra step of making a pit stop before returning to London Hospital, IMHO. The more people he could have encountered upon his way back to the Hospital...the more risk. Being seen leaving this bolthole,without the organs,without a knife,without any incriminating evidence, is still an additional risk. But thats just my opinion...not a fact, of course.

Considering that the concept of the return to the Hospital, as opposed to just departing it originally,being riskier, I'd tend to think that Stephenson had contemplated this risk factor and scrutinized whether returning immediately was safer than stopping off to leave the organs. Thats why I personally think he took them back with them. Proving this,of course, is impossible.

Finding a storage place at the Hospital probably wouldn't have been as hard as we think. With jars available to store organs in the Hospital, who knows ? Wrapped in towels perhaps...placed in some other sort of inconspicuous container...etc..etc..etcetera.

Bottom line Glenn...If RDS was the Ripper, his skills and knowledge of surgery would have made him more aware of arterial spray and such. Who's to say whether he didn't roll up his sleeves prior to eviscerating the women ?

Jeff...

I hear you buddy. I agree that Stephenson could or would have worked something out to insure his safe, but riskier, return. He would have had to !

Then we have the December PMG article that describes the attention given to the mysterious man who left London Hospital without notice by the police. The problem with this scenario is that the PMG article came 23 days after RDS signed himself out of London Hospital and going off to live in St Martins..... Did this letter sent to the gentleman involved with East End philanthropy come to him after December 9th and into the following week ? Because if it did,the letter was written after RDS was out of London Hospital,indicating that the police may not have made routine check-ups at the London Hospital, as no one from day or night security had their attention aroused enough to get the police involved....

|

Brad McGinnis

Inspector

Username: Brad

Post Number: 257

Registered: 4-2003

| | Posted on Saturday, July 30, 2005 - 11:29 pm: |

|

Yo! How! Is it as hot in Philly as in the western mountains? Maybe I can answer some of your questions. I work in an 138 bed nursing home. Ok its a true nursing home and not an "Old folks" home. With todays hospitials pushing people out while theyre still bleeding because the insurance Co.s wont pay, our patients are sometimes quite young. Some 20s and 30s...accidents, some 30s and 40s...cancer and other catastrophic illnesses. Point is the acuity (severity of patient illness) of a nursing facility is now the equivalient of a hospitial twenty years ago.

On weekends, starting Friday nite at 10 there are 13 or 14 people, all nursing staff, in the whole building...4 floors. In addition there is a wing of the second floor called Independant Living. These are folks (like RS who arent needing critical care) who can come and go as they like. The entrance to their wing (which contains 20 suites) is unvideo monitored and they have a key. This is totally seperated from the 138 beds of critical care. Could RS had a similar kind of room? If you think of it, 13 people who have their hands full taking care of critical patients arent going to notice a resident who is amblitory and a common sight especially if RS was a nite person. I also have to believe the caregiver to patient ratio would have been less in 1888 than it is now. If RS was a patient who liked to talk to the staff and liked to wander at night he could pretty much come and go as he liked. In regard to blood stains, there need'nt be any. In most cases JTR sliced the vega nerve on the first stroke, thus stopping the heart beat instantly. Also I believe he garroted the vics, (not strangled) which would induce unconscienceness in about 7 seconds, via stopping the flow of blood to the brain by compressing the carotid artery and also slowing the heart beat. Think also of who was the security in facitities up until maybe 10 years ago....usually retired cops who needed their sleep...if indeed hospitials in 1888 had security. Anyway, keep searching How, the answer is out there somewhere. |

Jeffrey Bloomfied

Chief Inspector

Username: Mayerling

Post Number: 771

Registered: 2-2003

| | Posted on Saturday, July 30, 2005 - 11:58 pm: |

|

Hi all,

Glenn - nice points you brought up. And indeed, in bringing them up you demonstrate an old saw from one of the Sherlock Holmes stories - it is dangerous to arrive at conclusions when you have insufficient information. That is the problem here, and I admit, my statements to Howard earlier (which I thought were careful enough) did not take into consideration the issue of whether or not D'Onston would have notable amounts of blood on him (although Brad's point about the amount of blood being minimal at best due to the way the killings were committed is interesting - it too assumes perfect conditions for the killer's avoiding bloodstains each time - rather an unlikely scenario even if he were that careful (but then, is it equally probable about D'Onston being able to perfectly time his leaving and returning to the hospital on those four occasions (counting Stride and Eddowes as one occasion).

Thanks Howard for your kind comments, but Glenn's points are valid. I won't say back to the drawing board, but very careful consideration is needed here.

Glenn, I wonder about the trophy problem here. I don't if it would work, but there might be one place in the hospital itself where trophies (like a human kidney) might be stored for awhile if security was lax in some respects - in the pathology lab! It really seems to me to be stretching things, but if D'Onston studied the hospital situation before he began collecting his trophies - say he visited the pathology lab while in the hospital like people go into a lounge to chat to visitors or to read a book or newspaper - as something to while away his time.

He goes into the lab (if the hospital doesn't object). He chats to the pathology staff - he is an ex-doctor. They show him some of the specimens they have saved. He notes where they keep the spare specimen jars and the spirits they preserve them in. He notes how the door is secured (or not). And - if it is relatively simple - all he has to do is go into the lab when he returns with, say a kidney, and put it into a bottle with preservative. He might even specially label it. This is of course totally imaginary, and depends on too many ifs, but I wonder if something like this could have been possible. And after he leaves the hospital he can always (hopefully) return to visit his friends in the lab and see the his trophies on the sly.

Best wishes,

Jeff |

Brad McGinnis

Inspector

Username: Brad

Post Number: 258

Registered: 4-2003

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 12:14 am: |

|

Hi Jeff, may we consider another point? Perhaps the taking of the trophy was the point, not keeping it. Perhaps he tossed it away a block or two later in distain of the vic. Perhaps it was the taking rather than the keeping that drove him. Just a thought....Brad.

|

Harry Mann

Detective Sergeant

Username: Harry

Post Number: 129

Registered: 1-2005

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 5:07 am: |

|

Howard,

An added dificulty might be the location of the ward.Any idea on which floor the ward was situated?

I myself do not rule out what may seem to be an almost impossible situation,and I have no knowledge of the London Hospital layout,but the visiting rights in 1888,and the discipline of staff,were different.As I said it would be difficult to be absent for any length of time in those days.

I was once asked if a fully loaded tanker could smuggle an extra twenty thosand tons of oil.I thought that impossible,but I was shown how it could be done.So I seldom say impossible to anything.

Regards. |

Glenn G. Lauritz Andersson

Assistant Commissioner

Username: Glenna

Post Number: 3830

Registered: 8-2003

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 5:42 am: |

|

Hi Brad,

You're missing some of the valid points.

As has been put forward earlier, this occurred at night and early morning when one would assume there was little activity in the hospital, and which would also make it easier for any inmate to blend in among other patients or visitors.

The point is not whether or not D'Onston could come and go as he pleased, because I would expect that to be the case anyway.

The point is that the staff might put two and two together, if D'Onston would be noticed to pop up at strange hours on the murder dates. Most people followed the news of the murders quite closely since many papers made a big story out of it.

As for no traces of blood, I have always considered that a strange argument. That issue has generally been raised when stating that he mustn't necessarily have been COVERED in or sprayed with blood. And I agree he didn't need to be, and probably wasn't.

But that is not the point. Of course such mutilations -- even considering an early stop of blood flow in the body -- would be more or less impossible to do without messing up parts of the hands and the clothes, and especially since he also was carrying organs. To state that the killer would come out of that without any traces of blood and matter, is a total fantasy.

I would say this creates far too many obstacles. A killer like Jack the Ripper would most likely live under secluded circumstances, and personally I don't see him as a person that would be able to indulge in longer social conversations, chatting with the staff or anyone else. One of the reasons for him not getting caught is in my opinion that he kept much to himself and most probably were a loner.

All in all, considering how closely the general public read about and followed the murders in the paper, I think the whole scenario of popping in and out of a hospital or any other institution with a lot of people about (and no one begins to wonder), is -- although not impossible -- way too risky.

After all, loads of people came forward accusing neighbours and lodgers for behaving strangely the nights on the murder. People were alert, to say the least.

Just two more points, Brad:

"Perhaps the taking of the trophy was the point, not keeping it. Perhaps he tossed it away a block or two later in distain of the vic. Perhaps it was the taking rather than the keeping that drove him."

Well, regardless of the purpose of taking trophees (cannibalism, sexual satisfaction, collection etc.), I have never heard of a serial killer taking trophees just for the sake of the taking as such. That makes no sense. A killer generally takes them because he needs them for some special purpose, and they keep them in their closest vicinity, as close as possible in order to be able to enjoy them.

"Also I believe he garroted the vics, (not strangled) which would induce unconscienceness in about 7 seconds, via stopping the flow of blood to the brain by compressing the carotid artery and also slowing the heart beat."

I don't think so. Garroting would leave clearer marks on the neck, even for a shorter period of time, and there are no such evidence on the bodies. In my mind the killer may have used their own scarves to smother them with or used some kind of pressure against the throat on the right spot, which doesn't take much force and doesn't leave any marks whatsoever.

Although the relatively little amount of blood on the crime scenes may suggest it, we can't be certain that the victims were dead before their throats were cut; they could just as well have been smothered unconscious. As far as I know, this is a question that is still under open debate.

As I said, I do not have the proper knowledge about how hospitals of the day worked in Britain, but some scenarios in this context seems in my head to stretch things a bit beyond what appeals to my common sense. I could be wrong, though.

All the best

(Message edited by Glenna on July 31, 2005)

G. Andersson, writer/crime historian

Sweden

The Swedes are the men That Will not be Blamed for Nothing

|

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 754

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 9:47 am: |

|

Brad.....The humidity was the worst I have ever experienced on last Mon-Wed. I had to come home from work twice. Playing havoc with my blood pressure. I may have to rent a bed at the facility you work at.

Thanks for mentioning what you did. I don't and never did, see any problem for RDS leaving the Hospital. Taking your comments into consideration,its also possible,but much more risky,considering the atmosphere at the time,for him to return as easily as leaving.

Harry.....It was on the second floor,sir. And its true, where there is a will there is a way...almost nothing is impossible.

Jeff...Glenn does bring up a valid point,as usual,in his mentioning blood stains and such. Its just that for Stephenson to have been the Ripper or any other person not living alone or in seclusion from others, for RDS or anyone else to re-appear at a hospital,house,or where ever else covered with or partially covered with blood isn't very logical on the killer, not Glenn's, part. Of course Glenn is right..it doesn't make sense and would prove fatal to the Ripper's intentions.

Glenn: I agree with you, for what its worth, that serial killers take items for a reason, both for trophy-motive and other,often trivial, reasons. Bianchi gave rings and jewelry to women from the victims of his killings, as an example. Ritual murderers are like that too.

The point is that the staff might put two and two together, if D'Onston would be noticed to pop up at strange hours on the murder dates.

Thats the crux of the matter,Glenn, in a nutshell.

Have you moved yet? Are you eating eels yet ?

|

Glenn G. Lauritz Andersson

Assistant Commissioner

Username: Glenna

Post Number: 3831

Registered: 8-2003

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 11:34 am: |

|

Howie, old boy.

No, I'll be moving on August 24. After that I'll be an distinguished Englishman and not a crazy Swede, at least in practice. Maybe I'll still be crazy, though...

No way in the world will I come near those 'yellied eels'. You can be sure of that.

All the best

G. Andersson, writer/crime historian

Sweden

The Swedes are the men That Will not be Blamed for Nothing

|

Robert Charles Linford

Assistant Commissioner

Username: Robert

Post Number: 4740

Registered: 3-2003

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 11:40 am: |

|

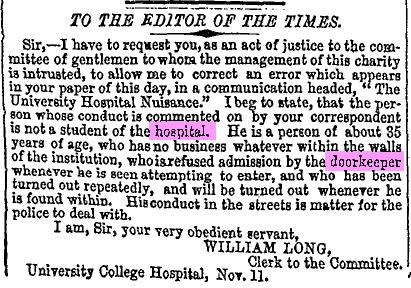

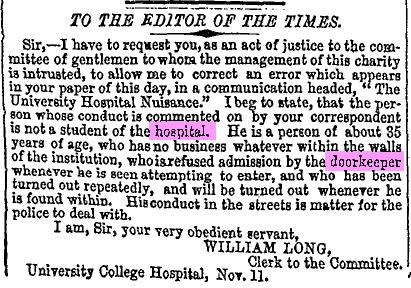

This doesn't tell us about 1888, but I'm posting it anyway.

NOV 12th 1844

Robert |

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 755

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 11:52 am: |

|

Robert Chazz:

Thanks very much for this piece..very much.

Maybe I should contact the London Hospital and ask them if they had a doorman stationed on day and night shift during the 1880's. Not only that,but if they had a back door that allowed accessibility to the Hospital. I don't have a schematic or blueprint to look at of the Hospital.

That of course doesn't mean that someone could not have bypassed the front door or back door security, but this find of yours proves they had front door security prior to 1888...

What it does do is show and practically guarantee that had RDS been seen going in the Hospital via an alternative method, the proverbial merde would have hit the fan.

Hope Uncle Linford is doing well....thanks again R.C. !!! |

Sir Robert Anderson

Inspector

Username: Sirrobert

Post Number: 489

Registered: 2-2003

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 12:20 pm: |

|

How - just throwing out a thought, and not saying it's the most reasonable answer, but...

What about RDS walking out the door during the day, when there was a lot of foot traffic, spending the night in a bolthole, and coming back the next day when once again there was more ebb and flow and he was all neat and clean ?

If you think about it, it would have given him a great alibi: "Where were you on the night of ----". "Right here in the hospital, Sor, I mean Sir...check the records."

Sir Robert

'Tempus Omnia Revelat'

SirRobertAnderson@gmail.com

|

Restless Spirit

Detective Sergeant

Username: Judyj

Post Number: 79

Registered: 2-2005

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 1:14 pm: |

|

Hi All

With respect to Stephenson and his leaving the hosp unnoticed. Is it possible that he was able to steal doctor's garb, with little skull cap and mask for mouth. No one would have recognized him plus if he hid these garments and donned them on his return, no one would have noticed a doctor with blood on him. I realize my imagination may be running wild here, but I have seen this played out many times on TV, why not in real life.

Just a thought.

regards

Restless Spirit

|

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 757

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 2:51 pm: |

|

Sir Bob and Restless....

They're just as plausible as any other ideas,in my opinion...

Sir Bob's scenario means that RDS would come back the next morning. Okay..

This means that either no one checked the private ward he was in the previous night after he left...no one missed him [ could he have been in a private room in the private ward ? ] and no one was alarmed when he came back the next day. And why should they? They didn't know he was gone in the first place.

Combined with Restless's ideas, that could be possible. Julie..nothing's etched in stone in the "D'onston leaves the Hospital" saga. He could have done just that. Stealing doctor gear and looking like one himself...that might have worked.

Any countering these ideas?

P.S. I forgot to edit a post a while back. I forgot to mention that we should also probably consider Thursday night as a possible time of departure for RDS, as Kelly died in the morning of Friday,Nov. 9th. I remembered R.J.Palmer mentioning this a long time ago to me.

(Message edited by howard on July 31, 2005) |

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 759

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Sunday, July 31, 2005 - 9:02 pm: |

|

Brad.......Tim Mosley mentioned the idea you had before..

"Perhaps the taking of the trophy was the point, not keeping it. Perhaps he tossed it away a block or two later in distain of the vic."

...and suggested that perhaps a nearby outhouse could have been the inevitable resting place of the organs...

You could be right Brad....thats whats so intriguing about this case...the uncertainty.

Of course,it could drive a good man or woman to drink,the frustration of the volume of uncertainties...

...like you 'n me need a reason to bend an elbow,huh? |

Harry Mann

Detective Sergeant

Username: Harry

Post Number: 130

Registered: 1-2005

| | Posted on Monday, August 01, 2005 - 5:30 am: |

|

Howard,

Almost anything is not impossible.Here is a little tale to illustrate.Perhaps a lot of you have visited Bermuda,and walked as far as the garrison on top of the hill outside Hamilton.

I was stationed there 1947/48.The guardroom was situated at the entrance to camp.There was a sentry on duty outside,a sergeant, corporal and two other sentries inside.There was only one door giving entrance and exit.From the main room there was a door giving access to the cells.Both cells were occupied,one defaulter in each cell.The cells each had one small,iron barred window.Impossible to leave without being noticed.Yet the two defaulters managed to leave without being seen,and would probably have returned unnoticed,had they not got into trouble with the local police.You may imagine the consternation when the local police phoned one night and stated the defaulters were in another lock up in town.

The guards were not asleep,no saw was used to cut the bars,and no help was given in any manner.

Never underestimate the clever person,and no,I was not one of the two. |

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 760

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Monday, August 01, 2005 - 4:32 pm: |

|

Dear Mr. Mann...

So...I..er..I guess they never put you on guard duty again,huh?

Yes sir..this is a good analogy to our Stephenson issue...and a lot more difficult to pull off. It probably happens a lot without the offending party [ies] ever being noticed. Makes one think that RDS could have pulled it off. |

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 761

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Monday, August 01, 2005 - 4:36 pm: |

|

We know that Stephenson was sharing the same private ward as a Doctor Evans back in '88. [ its in the A-Z...]

One question for you Londoners or other British folks who have made the trip to London Hospital...Sharing the same private ward doesn't mean that they shared the same room in that ward, the Davis Ward,does it? |

Restless Spirit

Detective Sergeant

Username: Judyj

Post Number: 80

Registered: 2-2005

| | Posted on Tuesday, August 02, 2005 - 2:55 pm: |

|

Howard

I see you haven't forgotten my name, nice to be remembered. How is Ivan these days?

Thanks for replying and not telling me what a goof I am. But the idea appealed to me due to his obvious cunningness. He appears to have been able to come up with some incredible stories at times true or not. I also think he was charming enough to pull it off.Who knows he may have even treated patients, again, masked. He was a smart cookie,dressed reasonably well, could pass for a professional (doctor,lawyer ,merchant etc)and I really believe he could charm a snake. It is of course also possible, if this scenerio were representing the actual events, that he was helped,by an unsuspecting nurse,patient etc. This of course is based on whether Stephenson was indeed the ripper, however my money right now is on Cutbush (rightly or wrongly)

Many regards

Restless Spirit

|

Howard Brown

Chief Inspector

Username: Howard

Post Number: 764

Registered: 7-2004

| | Posted on Tuesday, August 02, 2005 - 7:42 pm: |

|

Julie....

You aren't a goof for posting ideas ! Besides, I am the King of Goofs 'round these here parts...so back off ! The crown is still mine !

Having an accomplice isn't entirely farfetched either. Not necessarily an assistant,aiding and abetting him, but someone paid to keep their mouth shut on only 4 days out of 134 during his stay in the Hospital under the pretense of RDS going out for some "other reason" sounds possible to me. Look at Harry Mann's story of the guards on duty....Who would believe something like that? Yet it happened...and probably still does.

If Stephenson was as capable and imaginative in other areas or opportunities as he was in concocting the stories he wrote for Stead,he certainly could have persuaded some nurse or night crew personnel to believe in yet another story...on only 4 nights,mind you. A couple of coins of the realm wouldn't hurt if they were offered either..

I believe you mean "Ivor" not "Ivan". The former is fine,I think...the latter was Terrible.... |

c.d.

Unregistered guest

| | Posted on Monday, August 01, 2005 - 11:22 am: |

|

Just a couple of points. Where there is a will there is a way. Stephenson was a smart and clever individual and a couple of bribes can work wonders. |

Tee@jtrforums

Unregistered guest

| | Posted on Saturday, July 30, 2005 - 9:01 pm: |

|

Hi all,

remember that DOnston had been there for the month proceeding these murders and so had time to familiarize himself with the Hospital itself, the staff, their shifts, there personalities, and he also had the time to build a rapport with them. This is easy to do in a Hospital where everyone gets familar with each-other rather quickly.

Also DOnston's illness at the time "Neurosthenia" (Not Chloralism!) was not a serious one, and was something that fresh(ish) air was prescribed for, and it was seen as good for his ailment. Day or night.

DOnston was also a regular smoker of a pipe. So he had time to build a ritual (excuse the pun) off going outside to either stretch his legs, Smoke his pipe. Or to just get some fresh air.

He was also a former Military Surgeon and a self titled Doctor of some kind, so he was probably seen as "one of them".

And once Nichols and Chapman had been killed the press were all over Whitechapel for the scoop.

DOnston too was a Journalist, and for a rather large respectable publication. So he could of used that as a cover in itself to get out of the hospital at times?

And Glenn we dont really know If the murderer was indeed covered in blood. I somehow doubt he was. But even so it wasn`t really the day and age of DNA marvels and so wouldn`t of meant that much at all. What with Slaughterhouses being rather plentyful in the local area. Apart from helping him to stand out from the usual milling crowds of Whitechapel. Also I dont know if you have seen the images here or on jtrforums? (kindly posted by Jane Coram) the images of the types of detachable Cuff and Collars that were available at the time of these killings? They are just amazing. Some seem like they`re almost "built for the kill" being made from a quick wipe clean plastic. So we really have no idea whether he was or whether he wasn`t blood spattered.

All the best.

Tee. |

Tee@jtrforums

Unregistered guest

| | Posted on Friday, July 29, 2005 - 10:11 pm: |

|

By all means delete or not post if too long.

I thought I`d post this as it is a non-Ripper related chapter regarding The London Hospital at the time of Stephenson's stint at the same Hospital. It may be of interest ?

^^ The Elephant Man

by Sir Frederick Treves

Here, good reader, as your reward for having read this book to the end, is one of the most extraordinary true stories ever told about a human oddity��The Ele-phant Man,� by Sir Frederick T�reves.

The Elephant Man, John Merrick, lived a short life. For most of his twenty-seven years he was an object of horror to those who saw him. His affliction, neuro-fibromatosis, caused tumors to grow around the nerves under his skin and in his bones. His body was so gro-tesque that he did not dare to show himself on the streets. When he went out, he wore a hat with a hood that covered his face, and a loose cloak that hid his strange form.

Merrick�s disease was the result of a spontaneous genetic change. It could not be treated. He was taken from town to town by itinerant showmen, who exploited him cruelly. In 1884, to Merrick�s great good fortune, he made the acquaintance of Frederick Treves.

Treves, one of the most gifted medical men of that day, included among his clients the British royal family; he was Surgeon Extraordinary to Queen Victoria. lie was also a talented man of letters. The doctor became the Elephant Man�s guardian angel, making the last five years of his life the happiest he ever lived. Long after Merrick�s death, Treves told his story in his book The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences. (The head-ings are mine.)�F.D.

In the Mile End Road, opposite to the London Hospital, there was (and possibly still is) a line of small shops. Among them was a vacant greengrocer�s which was to let. The whole of the front of the shop, with the exception of the door, was hidden by a hanging sheet of canvas on which was the announcement that the Ele-phant Man was to be seen within and that the price of admission was twopence. Painted on the canvas in primitive colors was a life-size portrait of the Elephant Man. This very crude production depicted a frightful creature that could only have been possible in a night-mare. It was the figure of a man with the characteristics of an elephant. The transfiguration was not far ad-vanced. There was still more of the man than of the beast. This fact�that it was still human�was the most repellent attribute of the creature. There was nothing about it of the pitiableness of the misshapen or the de-formed, nothing of the grotesqueness of the freak, but merely the loathing insinuation of a man being changed into an animal. Some palm trees in the background of the picture suggested a jungle and might have led the imaginative to assume that it was in this wild that the perverted object had roamed.

When I first became aware of this phenomenon the exhibition was closed, but a well-informed boy sought the proprietor in a public house and I was granted a private view on payment of a shilling. The shop was empty and grey with dust. Some old tins and a few shrivelled potatoes occupied a shelf and some vague vegetable refuse the window. The light in the place was dim, being obscured by the painted placard outside. The far end of the shop�where I expect the proprietor sat at a desk�was cut off by a curtain or rather by a red tablecloth suspended from a cord by a few rings. The room was cold and dank, for it was the month of November. The year, I might say, was 1884. The showman pulled back the curtain and re- vealed a bent figure crouching on a stool and covered by a brown blanket. In front of it, on a tripod, was a large brick heated by a Bunsen burner. Over this the creature was huddled to warm itself. It never moved when the curtain was drawn back. Locked up in an empty shop and lit by the faint blue light of the gas jet, this hunched-up figure was the embodiment of lone-liness. It might have been a captive in a cavern or a wizard watching for unholy manifestations in the ghostly flame. Outside the sun was shining and one could hear the footsteps of the passers-by, a tune whistled by a boy and the companionable huni of traffic in the road.

The showman_speaking as if to a dog�called out harshly: �Stand up!� The thing arose slowly and let the blanket that covered its head and back fall to the ground. There stood revealed the most disgusting speci-men of humanity that I have ever seen. In the course of my profession I had come upon lamentable deformities of the face due to injury or disease, as well as mutila-tions and contortions of the body depending upon like causes; but at no time had I met with such a degraded or perverted version of a human being as this lone figure displayed. He was naked to the waist, his feet were bare, he wore a pair of threadbare trousers that had once belonged to some fat gentleman�s dress suit.

His Misshapen Head

From the intensified painting in the street I had imagined the Elephant Man to be of gigantic size. This, however, was a little man below the average height and made to look shorter by the bowing of his back. The most striking feature about him was his enormous and misshapen head. From the brow there projected a huge bony mass like a loaf, while from the back of the head hung a bag of spongy, fungous-looking skin, the surface of which was comparable to brown cauliflower. On the top of the skull were a few long lank hairs. The osseous growth on the forehead almost occluded one eye. The circumference of the head was no less than that of the man�s waist. From the upper jaw there pro-jected another mass of bone. It protruded from the mouth like a pink stump, turning the upper lip inside out and making of the mouth a mere slobbering aper-ture. This growth from the jaw had been so exaggerated in the painting as to appear to be a rudimentary trunk or tusk. The nose was merely a lump of flesh, only rec- ognizable as a nose from its position. The face was no more capable of expression than a block of gnarled wood. The back was horrible, because from it hung, as far down as the middle of the thigh, huge, sack-like masses of flesh covered by the same loathsome cauli-flower skin.

A Fin Rather Than a Hand

The right arm was of enormous size and shapeless. It suggested the limb of the subject of elephantiasis. It was overgrown also with pendent masses of the same cauliflower-like skin. The hand was large and clumsy�a fin or paddle rather than a hand. There was no distinction between the palm and the back. The thumb had the appearance of a radish, while the fingers might have been thick, tuberous roots. As a limb it was almost useless. The other arm was remarkable by con-trast. It was not only normal but was, moreover, a deli-cately shaped limb covered with fine skin and provided with a beautiful hand which any woman might have en-vied. From the chest hung a bag of the same repulsive flesh. It was like a dewlap suspended from the neck of a lizard. The lower limbs had the characters of the de-formed arm. They were unwieldy, dropsical looking and grossly misshapen.

To add a further burden to his trouble the wretched man, when a boy, developed hip disease, which had left him permanently lame, so that be could only walk with a stick. He was thus denied all means of escape from his tormentors. As he told me later, he could never run away. One other feature must be men-tioned to emphasize his isolation from his kind. Al-though he was already repellent enough, there arose from the fungous skin-growth with which he was almost covered a very sickening stench which was hard to tolerate. From the showman I learnt nothing about the Elephant Man, except that he was English, that his name was John Merrick and that he was twenty-one years of age.

His Disguise

As at the time of my discovery of the Elephant Man I was the Lecturer on Anatomy at the Medical College opposite, I was anxious to examine him in de-tail and to prepare an account of his abnormalities. I therefore arranged with the showman that I should in-terview his strange exhibit in my room at the college. I became at once conscious of a difficulty. The Elephant Man could not show himself in the streets. He would have been mobbed by the crowd and seized by the po-lice. He was, in fact, as secluded from the world as the Man with the Iron Mask. He had, however, a disguise, although it was almost as startling as he was himself. It consisted of a long black cloak which reached to the ground. Whence the cloak had been obtained I cannot imagine. I had only seen such a garment on the stage wrapped about the figure of a Venetian bravo. The re-cluse was provided with a pair of bag-like slippers in which to hide his deformed feet. On his head was a cap of a kind that never before was seen. It was black like the cloak, had a wide peak, and the general outline of a yachting cap. As the circumference of Merrick�s head was that of a man�s waist, the size of this headgear may be imagined. From the attachment of the peak a grey flannel curtain hung in front of the face. In this mask was cut a wide horizontal slit through which the wearer could look out. This costume, worn by a bent man hobbling along with a stick, is probably the most re-markable and the most uncanny that has as yet been designed. I arranged that Merrick should cross the road in a cab, and to insure his immediate admission to the college I gave him my card. This card was destined to play a critical part in Merrick�s life.

I made a careful examination of my visitor the result of which I embodied in a paper. I made little of the man himself. He was shy, confused, not a little frightened and evidently much cowed. Moreover, his speech was almost uninteffigible. The great bony mass that projected from his mouth blurred his utterance and made the articulation of certain words impossible. He returned in a cab to the place of exhibition, and I as-sumed that I had seen the last of him, especially as I found next day that the show had been forbidden by police and that the shop was empty.

Shunned like a Leper

I supposed that Merrick was imbecile and had been imbecile from birth. The fact that his face was in-capable of expression, that his speech was a mere splut-tering and his attitude that of one whose mind was void of all emotions and concerns gave grounds for this be-lief. The conviction was no doubt encouraged by the hope that his intellect was the blank I imagined it to be.

That he could appreciate his position was unthinkable. Here was a man in the heyday of youth who was so vilely deformed that everyone he met confronted him with a look of horror and disgust. He was taken about the country to be exhibited as a monstrosity and an ob-ject of loathing. He was shunned like a leper, housed like a wild beast, and got his only view of the world from a peephole in a showman�s cart. He was, more-over, lame, had but one available arm, and could hardly make his utterances understood. It was not until I came to know that Merrick was highly inteffigent, that he possessed an acute sensibility and�worse than all�a romantic imagination that I realized the overwhelming tragedy of his life.

The episode of the Elephant Man was, I imagined, closed; but I was fated to meet him again�two years later�under more dramatic conditions. In England the showman and Merrick had been moved on from place to place by the police, who considered the exhibition degrading and among the things that could not be al-lowed. It was hoped that in the uncritical retreats of Mile End a more abiding peace would be found. But it was not to be. The official mind there, as elsewhere, very properly decreed that the public exposure of Merrick and his deformities transgressed the limits of de-cency. The show must close.

Merrick Is Robbed

The showman, in despair, fled with his charge to the Continent. Whither he roamed at first I do not know, but he came finally to Brussels. His reception was discouraging. Brussels was firm; the exhibition was banned; it was brutal, indecent and immoral, and could not be permitted within the confines of Belgium. Mer-rick was thus no longer of value. He was no longer a source of profitable entertainment. He was a burden. He must be got rid of. The elimination of Merrick was a simple matter. He could offer no resistance. He was as docile as a sick sheep. The impresario, having robbed Merrick of his paltry savings, gave him a ticket to London, saw him into the train and no doubt in part-ing condemned him to perdition. His destination was Liverpool Street. The journey may be imagined. Merrick was in his alarming outdoor garb. He would be harried by an eager mob as he hobbled along the quay. They would run ahead to get a look at him. They would lift the hem of his cloak to peep at his body. He would try to hide in the train or in some dark corner of the boat, but never could he be free from that ring of curious eyes or from those whispers of fright and aversion. He had but a few shillings in his pocket and nothing either to eat or drink on the way. A panic-dazed dog with a label on his collar would have received some sympathy and possibly some kindness. Merrick received none.

What was he to do when he reached London? He had not a friend in the world. He knew no more of London than he knew of Peking. How could he find a lodging, or what lodging-house keeper would dream of taking him in? All he wanted was to hide. What most he dreaded were the open street and the gaze of his fel-low-men. If even he crept into a cellar the horrid eyes and the still more dreaded whispers would follow him to its depths. Was there ever such a homecoming!

Rescued by the Police

At Liverpool Street he was rescued from the crowd by the police and taken into the third-class wait-ing-room. Here he sank on the floor in the darkest corner. The police were at a loss what to do with him.

They had dealt with strange and mouldy tramps, but never with such an object as this. He could not explain himself. His speech was so maimed that he might as well have spoken in Arabic. He had, however, some-thing with him which he produced with a ray of hope. It was my card. The card simplified matters. It made it evident that this curious creature had an acquaintance and that the individual must be sent for. A messenger was dispatched to the London Hospital which is compara-tively near at hand. Fortunately I was in the building and returned at once with the messenger to the station.

In the waiting-room I had some difficulty in making a way through the crowd, but there, on the floor in the corner, was Merrick. He looked a mere heap. It seemed as if he had been thrown there like a bundle. He was so huddled up and so helpless looking that he might have had both his arms and his legs broken. He seemed pleased to see me, but he was nearly done. The journey and want of food had reduced him to the last stage of exhaustion. The police kindly helped him into a cab, and I drove him at once to the hospital. He appeared to be content, for he fell asleep almost as soon as he was seated and slept to the journey�s end. He never said a word, but seemed to be satisfied that all was well.

In the Hospital

In the attics of the hospital was an isolation ward with a single bed. It was used for emergency pur-poses�for a case of delirium tremens, for a man who had become suddenly insane or for a patient with an undetermined fever. Here the Elephant Man was de-posited on a bed, was made comfortable and was sup-plied with food. I had been guilty of an irregularity in admitting such a case, for the hospital was neither a ref-uge nor a home for incurables. Chronic c~ises were not accepted, but only those requiring active treatment, and Merrick was not in need of such treatment. I applied to the sympathetic chairman of the committee, Mr. Carr Gomm, who not only was good enough to approve my action but who agreed with me that Merrick must not again be turned out into the world.

Mr. Carr Gomm wrote a letter to The Times de-tailing the circumstances of the refugee and asking for money for his support. So generous is the English pub-lic that in a few days�I think in a week�enough money was forthcoming to maintain Merrick for life without any charge upon the hospital funds. There chanced to be two empty rooms at the back of the hospital which were little used. They were on the ground floor, were out of the way, and opened upon a large courtyard called Bedstead Square, because here the iron beds were marshalled for cleaning and painting. The front room was converted into a bed-sitting room and the smaller chamber into a bathroom. The condition of Merrick�s skin rendered a bath at least once a day a necessity, and I might here mention that with the use of the bath the unpleasant odor to which I have referred ceased to be noticeable. Merrick took up his abode in the hospital in December 1886. Merrick had now something he had never dreamed of, never supposed to be possible�a home of his own for life. I at once began to make myself acquainted with him and to endeavor to understand his mentality. It was a study of much interest. I very soon learned his speech so that I could talk freely with him. This afforded him great satisfaction, for, curiously enough, he had a pas-sion for conversation, yet all his life had had no one to talk to. I�having then much leisure�saw him almost every day, and made a point of spending some two hours with him every Sunday morning when he would chatter almost without ceasing. It was unreasonable to expect one nurse to attend to him continuously, but there was no lack of temporary volunteers. As they did not all acquire his speech it came about that I had occa-sionally to act as an interpreter.

Both a Child and a Man

I found Merrick, as I have said, remarkably intelli-gent. He had learned to read and had become a most voracious reader. I think he had been taught when he was in hospital with his diseased hip. His range of books was limited. The Bible and Prayer Book he knew intimately, but he had subsisted for the most part upon newspapers, or rather upon such fragments of old jour-nals as he had chanced to pick up. He had read a few stories and some elementary lesson books, but the de-light of his life was a romance, especially a love ro-mance. These tales were very real to him, as real as any narrative in the Bible, so that he would tell them to me as incidents in the lives of people who had lived. In his outlook upon the world he was a child, yet a child with some of the tempestuous feelings of a man. He was an elemental being, so primitive that he might have spent the twenty-three years of his life immured in a cave.

The Elephant Man�s Mother

Of his early days I could learn but little. He was very loath to talk about the past. It was a nightmare, the shudder of which was still upon him. He was born, he believed, in or about Leicester. Of his father he knew absolutely nothing. Of his mother he had some memory. It was very faint and had, I think, been elabo-rated in his mind into something definite. Mothers figured in the tales he had read, and he wanted his mother to be one of those comfortable lullaby-singing persons who are so lovable. In his subcons~tious mind there was apparently a germ of recollection in which someone figured who had been kind to him. He clung to this conception and made it more real by invention, for since the day when he could toddle no one had been kind to him. As an infant he must have been repellent, although his deformities did not become gross until he had attained his full stature.

It was a favorite belief of his that his mother was beautiful. The fiction was, I am aware, one of his own making, but it was a great joy to him. His mother, lovely as she may have been, basely deserted him when he was very small, so small that his earliest clear memories were of the workhouse to which he had been taken. Worthless and inhuman as this mother was, he spoke of her with pride and even with reverence. Once, when referring to his own experience, he said: �It is very strange, for, you see, mother was so beautiful.�

Mocked by the Mob

The rest of Merrick�s life up to the time that I met him at Liverpool Street Station was one dull record of degradation and squalor. He was dragged from town to town and from fair to fair as if he were a strange beast in a cage. A dozen times a day he would have to expose his nakedness and his piteous deformities before a gaping crowd who greeted him with such mutterings as �Oh! what a horror! What a beast!� He had had no childhood. He had had no boyhood. He had never ex-perienced pleasure. He knew nothing of the joy of living nor of the fun of things. His sole idea of hap-piness was to creep into the dark and hide. Shut up alone in a booth, awaiting the next exhibition, how mocking must have sounded the laughter and merri-ment of the boys and girls outside who were enjoying the �fun of the fair�! He had no past to look back upon and no future to look forward to. At the age of twenty he was a creature without hope. There was nothing in front of him but a vista of caravans creeping along a road, of rows of glaring show tents and of circles of staring eyes with, at the end, the spectacle of a broken man in a poor law infirmary. Those who are interested in the evolution of char-acter might speculate as to the effect of this brutish life upon a sensitive and intelligent man. It would be rea-sonable to surmise that he would become a spiteful and malignant misanthrope, swollen with venom and filled with hatred of his fellow-men, or, on the other hand, that he would degenerate into a despairing melancholic on the verge of idiocy. Merrick, however, was no such being. He had passed through the fire and had come out unscathed. His troubles had ennobled him. He showed himself to be a gentle, affectionate and lovable creature, as amiable as a happy woman, free from any trace of cynicism or resentment, without a grievance and without an unkind word for anyone. I have never heard him complain. I have never heard him deplore his ruined life or resent the treatment he had received at the hands of callous keepers. His journey through life had been indeed along a via dolorosa, the road had been uphill all the way, and now, when the night was at its blackest and the way most steep, he had suddenly found himself, as it were, in a friendly inn, bright with light and warm with welcome. His gratitude to those about him was pathetic in its sincerity and eloquent in the childlike simplicity with which it was expressed.

A Pariah and an Outcast

As I learned more of this primitive creature I found that there were two anxieties which were promi-nent in his mind and which he revealed to me with diffi-dence. He was in the occupation of the rooms assigned to him and had been assured that he would be cared for to the end of his days. This, however, he found hard to realize, for he often asked me timidly to what place he would next be moved. To understand his attitude it is necessary to remember that he had been moving on and moving on all his life. He knew no other state of existence. To him it was normal. He had passed from the workhouse to the hospital, from the hospital back to the workhouse, then from this town to that town or from one showman�s caravan to another. He had never known a home nor any semblance of one. He had no possessions. His sole belongings, besides his clothes and some books, were the monstrous cap and the cloak. He was a wanderer, a pariah and an outcast. That his quar-ters at the hospital were his for life he could not under-stand. He could not rid his mind of the anxiety which had pursued him for so many years�where am Ito be taken next?

Another trouble was his dread of his fellow-men, his fear of people�s eyes, the dread of being always stared at, the lash of the cruel mutterings of the crowd. In his home in Bedstead Square he was secluded; but now and then a thoughtless porter or a wardmaid would open his door to let curious friends have a peep at the Elephant Man. It therefore seemed to him as if the gaze of the world followed him still.

Influenced by these two obsessions he became, during his first few weeks at the hospital, curiously uneasy. At last, with much hesitation, he said to me one day: �When I am next moved can I go to a blind asylum or to a lighthouse?� He had read about blind asylums in the newspapers and was attracted by the thought of being among people who could not see. The lighthouse had another charm. It meant seclusion from the curious. There at least no one could open a door and peep in at him. There he would forget that he had once been the Elephant Man. There he would escape the vampire showman. He had never seen a lighthouse, but he had come upon a picture of the Eddystone, and it appeared to him that this lonely column of stone in the waste of the sea was such a home as he had longed for.

He Could Only Go Out After Dark

I had no great difficulty in ridding Merrick�s mind of these ideas. I wanted him to get accustomed to his fellow-men, to become a human being himself and to be admitted to the communion of his kind. He appeared day by day less frightened, less haunted looking, less anxious to hide, less alarmed when he saw his door being opened. He got to know most of the people about the place, to be accustomed to their comings and go-ings,, and to realize that they took no more than a friendly notice of him. He could only go out afte~r dark, and on fine nights ventured to take a walk in Bedstead Square clad in his black cloak and his cap. His greatest adventure was on one moonless evening when he walked alone as far as the hospital garden and back again.

To secure Merrick�s recovery and to bring him, as it were, to life once more, it was necessary that he should make the acquaintance of men and women who would treat him as a normal and intelligent young man and not as a monster of deformity. Women I felt to be more important than men in bringing about his trans-formation. Women were the more frightened of him, the more disgusted at his appearance and the more apt to give way to irrepressible expressions of aversion when they came into his presence. Moreover, Merrick had an admiration of women of such a kind that it at-tained almost to adoration. This was not the outcome of his personal experience. They were not real women but the products of his imagination. Among them was the beautiful mother surrounded, at a respectful distance, by heroines from the many romances he had read.

His Nurses

His first entry to the hospital was attended by a re-grettable incident. He had been placed on the bed in the little attic, and a nurse had been instructed to bring him some food. Unfortunately she had not been fully informed of Merrick�s unusual appearance. As she en-tered the room she saw on the bed, propped up by white pillows, a monstrous figure as hideous as an In-dian idol. She at once dropped the tray she was carry-ing and fled, with a shriek, through the door. Merrick was too weak to notice much, but the experience, I am afraid, was not new to him.

He was looked after by volunteer nurses whose ministrations were somewhat formal and constrained. Merrick, no doubt, was conscious that their service was purely-official, that they were merely doing what they were told to do and that they were acting rather as au-tomata than as women. They did not help him to feel that he was of their kind. On the contrary, they, with-out knowing it, made him aware that the gulf of separa-tion was immeasurable.

Feeling this, I asked a friend of mine, a young and pretty widow, if she thought she could enter Merrick�s room with a smile, wish him good morning and shake him by the hand. She said she could and she did. As he let go her hand he bent his head on his knees and sobbed until I thought he would never cease. The inter-view was over. He told me afterwards that this was the first woman who had ever smiled at him, and the first woman, in the whole of his life, who had shaken hands with him, From this day the transformation of Merrick commenced and he began to change, little by little, from a hunted thing into a man. It was a wonderful change to witness and one that never ceased to fas-cinate me.

Meeting the Nobility

Merrick�s case attracted much attention in the pa-pers, with the result that he had a constant succession of visitors. Everybody wanted to see him. He must have been visited by almost every lady of note in the social world. They were all good enough to welcome him with a smile and to shake hands with him. The Merrick whom I had found shivering behind a rag of a curtain in an empty shop was now conversant with duchesses and countesses and other ladies of high degree. They brought him presents, made his room bright with orna-ments and pictures, and, what pleased him more than all, supplied him with books. He soon had a large li-brary and most of his day was spent in reading. He was not the least spoiled; not the least puffed up; he never asked for anything; never presumed upon the kindness meted out to him and was always humbly and profound-ly grateful. Above all he lost his shyness. He liked to see his door pushed open and people to look in. He be-came acquainted with most of the frequenters of Bed-stead Square, would chat with him at his window and show them some of his choicest presents. He improved in his speech, although to the end his utterances were not easy for strangers to understand. He was beginning, moreover, to be less conscious of his unsightliness, a little disposed to think it was, after all, not so very ex-treme. Possibly this was aided by the circumstance that I would not allow a mirror of any kind in his room.

The height of his social development� was reached on an eventful day when Queen Alexandra�then Princess of Wales�came to the hospital to pay him a special visit. With that kindness which marked every act of her life, the Queen entered Merrick�s room smiling and shook him warmly by the hand. Merrick was transported with delight. This was beyond even his most extravagant dream. The Queen made many people happy, but I think no gracious act of hers ever caused such happiness as she brought into Merrick�s room when she sat by his chair and talked to him as to a per-son she was glad to see.

Unable to Smile or Sing

Merrick, I may say, was now one of the most con-tented creatures I have chanced to meet. More than once he said to me: �I am happy every hour of the day.� This was good to think upon when I recalled the half-dead heap of miserable humanity I had seen in the corner of the waiting-room at Liverpool Street. Most men of Merrick�s age would have expressed their joy and sense of contentment by singing or whistling when they were alone. Unfortunately poor Merrick�s mouth was so deformed that he could neither whistle nor sing. He was satisfied to express himself by beating time upon the pillow to some tune that was ringing in his head. I have many times found him so occupied when I have entered his room unexpectedly. One thing that al-ways struck me as sad about Merrick was the fact that he could not smile. Whatever his delight might be, his face remained expressionless. He could weep but he could not smile.

The Queen paid Merrick many visits and sent him every year a Christmas card with a message in her own handwriting. On one occasion she sent him a signed photograph of herself. Merrick, quite overcome, re-garded it as a sacred object and would hardly allow me to touch it. He cried over it, and after it was framed had it put up in his room as a kind of ikon. I told him that he must write to Her Royal Highness to thank her for her goodness. This he was pleased to do, as he was very fond of writing letters, never before in his life hav-ing had anyone to write to. I allowed the letter to be dispatched unedited. It began �My dear Princess� and ended �Yours very sincerely.� Unorthodox as it was it was expressed in terms any courtier would have envied.

Other ladies followed the Queen�s gracious exam-ple and sent their photographs to this delighted creature who had been all his life despised and rejected of men. His mantelpiece and table become so covered with pho-tographs of handsome ladies, with dainty knickknacks and pretty trifles that they may almost have befitted the apartment of an Adonis-like actor or of a famous tenor.

A Christmas Present for the Elephant Man

Through all these bewildering incidents and through the glamour of this great change Merrick still remained in many ways a mere child. He had all the in-vention of an imaginative boy or girl, the same love of �make-believe,� the same instinct of �dressing up� and of personating heroic and impressive characters. This attitude of mind was illustrated by the following in-cident. Benevolent visitors had given me, from time to time, sums of money to be expended for the comfort, of the ci-devant Elephant Man. When one Christmas was approaching I asked Merrick what he would like me to purchase as a Christmas present. He rather startled me by saying shyly that he would like a dressing-bag with silver fittings. He had seen a picture of such an article in an advertisement which he had furtively preserved. The association of a silver-fitted dressing-bag with the poor wretch wrapped up in a dirty blanket in an empty shop was hard to comprehend. I fathomed the mystery in time, for Merrick made little secret of the fancies that haunted his boyish brain. Just as a small girl with a tinsel coronet and a window curtain for a train will realize the conception of a countess on her way to court, so Merrick loved to imagine himself a dandy and a young man about town. Mentally, no doubt, he had frequently �dressed up� for the part. He could �make-believe� with great effect, but he wanted something to render his fancied character more realis-tic. Hence the jaunty bag which was to assume the function of the toy coronet and the window curtain that could transform a mite with a pigtail into a countess.

As a theatrical �property� the dressing-bag was in-genious, since there was little else to give substance to the transformation. Merrick could not wear the silk hat of the dandy nor, indeed, any kind of hat. He could not adapt his body to the trimly cut coat. His deformity was such that he could wear neither collar nor tie, while in association with his bulbous feet the young blood�s patent leather shoe was unthinkable. What was there left to make up the character? A lady had given him a ring to wear on his undeformed hand and a noble lord had presented him with a very stylish walking-stick. But these things, helpful as they were, were hardly sufficing. The dressing-bag, however, was distinctive, was explanatory and entirely characteristic. So the bag was obtained and Merrick the Elephant Man became, in the seclusion of his chamber, the Piccadilly exquisite, the young spark, the gallant, the �nut.� When I purchased the article I realized that as Merriclc could never travel he could hardly want a dressing-bag. He could not use the silver-backed brushes and the comb because he had no hair to brush. The ivory-handled razors were useless because he could not shave. The deformity of his mouth rendered an ordinary toothbrush of no avail, and as his monstrous lips could not hold a cigarette the cigarette-case was a mockery. The silver shoe-horn would be of no service in the putting on of his ungainly slippers, while the hat-brush was quite unsuited to the peaked cap with its visor. Still the bag was an emblem of the real swell and of the knockabout Don Juan of whom he had read. So every day Merrick laid out upon his table, with proud precision, the silver brushes, the razors, the shoe-horn and the silver cigarette-case, which I had taken care to fill with cigarettes. The contemplation of these gave him great pleasure, and such is the power of self-decep-tion that they convinced him he was the �real thing.�

The Elephant Man in Love

I think there was just one shadow in Merrick�s life. As I have already said, he had a lively imagination; he was romantic; he cherished an emotional regard for women and his favorite pursuit was the reading of love stories. He fell in love�in a humble and devotional way�with, I think, every attractive lady he saw. He, no doubt, pictured himself the hero of many a pas-sionate incident. His bodily deformity had left un-marred the instincts and feelings of his years. He was amorous. He would like to have been a lover, to have walked with the beloved object in the languorous shades of some beautiful garden and to have poured into her ear all the glowing utterances that he had re-hearsed in his heart. And yet�the pity of it!�imagine the feelings of such a youth when he saw nothing but a look of horror creep over\ the face of every girl whose eyes met his. I fancy when he talked of life among the blind there was a half-formed idea in his mind that he might be able to win the affection of a woman if only she were without eyes to see.

As Merrick developed he began to display certain modest ambitions in the direction of improving his mind and enlarging his knowledge of the world. He was as curious as a child and as eager to learn. There were so many things he wanted to know and to see. In the first place he was anxious to view the interior of what he called �a real house,� such a house as figured in many of the tales he knew, a house with a hail, a drawing-room where guests were received and a dining-room with plates on the sideboard and with easy chairs into which the hero could �fling himself.� The workhouse, the common lodging-house and a variety of mean gar-rets were all the residences he knew. To satisfy this wish I drove him up to my small house in Wimpole Street. He was absurdly interested, and examined ev-erything in detail and with untiring curiosity. I could not show him the pampered menials and the powdered footmen of whom he had read, nor could I produce the white marble staircase of the mansion of romance nor the gilded mirrors and the brocaded divans which belong to that style of residence. I explained that the house was a modest dwelling of the Jane Austen type, and as he had read Emma he was content.

A Visit to the Theater

A more burning ambition of his was to go to the theatre. It was a project very difficult to satisfy. A popular pantomime was then in progress at Drury Lane Theatre, but the problem was how so conspicuous a being as the Elephant Man could be got there, and how he was to see the performance without attracting the notice of the audience and causing a panic or, at least, an unpleasant diversion. The whole matter was most in-geniously carried through by that kindest of women and most able of actresses�Mrs Kendal. She made the necessary arrangements with the lessee of the theater. A box was obtained. Merrick was brought up in a carriage with drawn blinds and was allowed to make use of the royal entrance so as to reach the box by a private stair. I had begged three of the hospital sisters to don evening dress and to sit in the front row in order to �dress� the box, on the one hand, and to form a screen for Merrick on the other. Merrick and I occupied the back of the box which was kept in shadow. All went well, and no one saw a figure, more monstrous than any on the stage, mount the staircase or cross the corridor. One has often witnessed the unconstrained delight of a child at its first pantomime, but Merrick�s rapture was much more intense as well as much more solemn. Here was a being with the brain of a man, the fancies of a youth and the imagination of a child. His attitude was not so much that of delight as of wonder and amaze-ment. He was awed. He was enthralled. The spectacle left him speechless, so that if he were spoken to he took no heed. He often seemed to be panting for breath. I could not help comparing him with a man of his own age in the stalls. This satiated individual was bored to distraction, would look wearily at the stage from time to time and then yawn as if he had not slept for nights; while at the same time Merrick was thrilled by a vision that was almost beyond his comprehension. Merrick talked of this pantomime for weeks and weeks. To him, as to a child with the faculty of make-believe, every-thing was real; the palace was the home of kings, the princess was of royal blood, the fairies were as un-doubted as the children in the street, while the dishes at the banquet were of unquestionable gold. He did not like to discuss it as a play but rather as a vision of some actual world. When this mood possessed him he would say: �I wonder what the prince did after we left?� or �Do you think that poor man is still in the dungeon?� and so on and so on.