Borderland, April 1896.

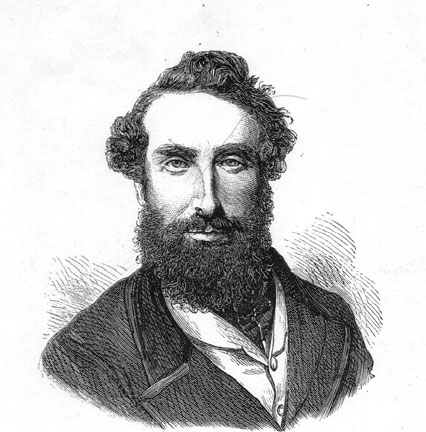

THE writer of the following extraordinary fragment of autobiography has been known to me for many years. He is one of the most remarkable persons I ever met. For more than a year I was under the impression that he was the veritable Jack the Ripper ; an impression which I believe was shared by the police, who, at least once had him under arrest ; although, as he completely satisfied them, they liberated him without bringing him into court. He wrote for me, while I was editing the Pall Mall Gazette, two marvellous articles on the Obeahism of West Africa, which I have incorporated with this article. The Magician, who prefers to be known by his Hermetic name of Tautriadelta, and who objects even to be called a magician, will undoubtedly be regarded by most people as Baron Munchausen Redivivus. He has certainly travelled in many lands, and seen very strange scenes.

I cannot, of course, vouch personally for the authenticity of any of his stories of his experiences. He has always insisted that they are literally and exactly true. When he sent me this MS., he wrote about it as follows:

" If you do chop it up, please do it by omitting incidents bodily. The evidence of an eyewitness deprived even of its trivialities is divested of its vraisemblance. If you leave them as I have written them, people will know, will feel, that they are true. Editing, I grant, may improve them as a literary work, but will entirely destroy their value as evidence, especially to people who know the places and persons."

I have therefore printed it as received, merely adding cross-heads.

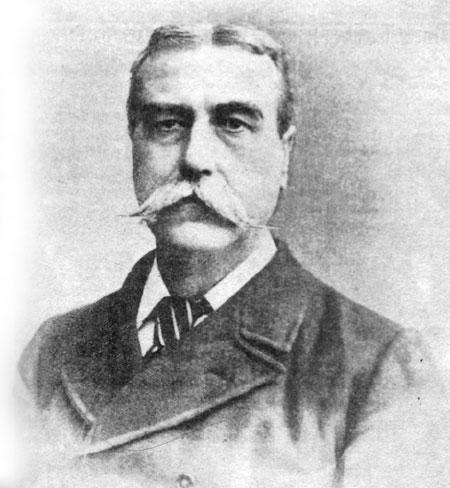

W.T. Stead

I was always, as a boy, fond of everything pertaining to mysticism, astrology, witchcraft, and what is commonly known as " occult science " generally ; and I devoured with avidity every book or tale that I could get hold of having reference to these arts. I remember, at the early age of 14, practising mesmerism on several of my schoolfellows particularly on my cousin, a year younger than myself. But on this boy (now, by the way, a hardheaded north country solicitor) developing a decided talent for somnambulism, and

nearly killing himself in one of his nocturnal rambles, my experiments in that direction were brought to an untimely close.

As a medical student. however, my interest in the effects of mind upon matter once more awoke, and my physiological studies and researches were accompanied by psychological experiments. I read Zanoni at this time with great zest, but I am afraid with very little understanding, and longed excessively to know its author; little dreaming that I should one day be the pupil of the great magist, Bulwer Lytton-the one man in modern times for whom all the systems of ancient and modern magism and magic, white and black, held back no secrets.

It was in the winter after the publication of the weird " Strange Story " in which the Master attempted to teach the world many new and important truths (under the veil of fiction) that I made the acquaintance at Paris of young Lytton, the son of (the then) Sir Edward. He was at that time, I suppose, about ten years my senior; and though passionately attached to his father, who was both father and mother to him, did not share my intense admiration and enthusiasm for his mystic studies and his profound lore.

Anyhow, in the spring following, he presented me to his father as an earnest student of occultism. I was then about an years of age, and I suppose Sir Edward was attracted to me partly by my irrepressible hero-worship, of which he was the object, and partly because he saw that I possessed a cool, logical brain and iron nerve ; and, above all, was genuinely, terribly in earnest.

I remember that the first time on which he condescended to teach me anything, he seated me before an egg-shaped crystal and asked me what I saw therein. For the first ten minutes I saw nothing and was somewhat discouraged, thinking that he would blame me for my inability ; but presently, to my astonishment and delight, I very plainly descried moving figures of men and animals. I described the scenes as they came into view, and the events that were transpiring; when, to my intense satisfaction-and I am afraid self-glorification-he said, " Why, you are a splendid fellow! you are just what I want.'

He then asked me if I would really like to seriously study Magism under his guidance. His words on this point are as fresh in my memory as ever. He said, " Remember, my boy, it will be very hard work, fatiguing to body and brain. There is no royal road, nothing but years of study and privation. Before you can conquer ' the powers ' you will have to achieve a complete victory over Self-in fact, become nothing more nor less than an incarnate intellect. Whatever knowledge you may gain, whatever powers you may acquire, can never be used for your advancement in the world, or for your personal advantage in any way. Even if you obtain the power of a King and the knowledge of a Prophet, you may have to pass your life in obscurity and poverty ; they will avail you nothing. Weigh well my words : three nights from this I will call you."

On the third evening, I never left my rooms after dinner, but lit up my pipe and remained anxiously awaiting Sir Edward's arrival. Hour after hour passed, but no visitor, and I determined to sit up all night, if need be, feeling that he would come.

He did ; but not in the way I expected. I happened to look up from the book which I was vainly attempting to read, and my glance fell upon the empty arm-chair on the other side of the fire-place. Was I dreaming, or did I actually see a filmy form, scarcely more than a shadow, apparently seated there? I awaited developments and watched. Second by second the film grew more dense until it became something like Sir Edward. I knew then that it was all right, and sat still as the form got more and more distinct, until at last it was apparently the Master himself sitting opposite to me-alive and in propri� person�. I instantly rose to shake hands with him ; but, as I got within touching distance, he vanished instantly. I knew then that it was only some variety of the Scin-Laeca that I had seen. It was my first experience of this, and I stood there in doubt what to do. Just then his voice whispered close to my ear, so close that I even felt his warm breath, "Come." I turned sharply round, but of course, no one was there.

I instantly put on my hat and greatcoat to go to his hotel, but when I got to the corner of the first street, down which I should turn to get there, his voice said, "Straight on." Of course, I obeyed implicitly. In a few minutes more, " Cross over" and, so guided, I came where he was. Where matters not ; but it was certainly one of the last places in which I should have expected to find him.

I entered, he was standing in the middle of the sacred pentagon, which he had drawn upon the floor with red chalk, and holding in his extended right arm the baguette, which was pointed towards me. Standing thus, he asked me if I had duly considered the matter and had decided to enter upon the course. I replied that my mind was made up. He then and there administered to me the oaths of a neophyte of the Hermetic lodge of Alexandria - the oaths of obedience and secrecy. It is self-evident that any further account of my experiences with Lord Lytton, or in Hermetic circles, is impossible.

But in my travels in the far East, and in Africa and elsewhere, I have met with many curious incidents connected with what Magists term "black magic," and also manifestations of psychic force and occult science as practised by other schools than that to which I belong ; and I will recall a few of them for the benefit of the readers of BORDERLAND.

The first of these was when I was studying chemistry under Dr. Allan (who was for so many years Baron Liebig's principal assistant at the great laboratory at the University of Giessen). Among the more advanced students was a Saxon named Karl Hoffmann, who was much given to the study of psychology, psychic force, and the effects of the magnetic current and odic force upon the nervous system. I need scarcely say that we fraternised, and soon became almost inseparable. One day we were talking of the "doppel-ganger," and he proceeded forthwith to illustrate his position. He told me that his doppel-ganger should visit a public ball which was to be held that night ; should speak to and dance with many persons to whom he was well known ; should spend three hours there, and yet that all the time his real body should be present with me in my rooms.

This was very interesting to me : because, although I knew how to produce the Scin-Laeca, and even the ordinary doppel-ganger, yet these were intangible and impalpable. But he was to shake hands with friends, drink with them, and hold others in his grasp during the dances, and I was impatient for the night to come. I employed the interval in making one or two little private arrangements unknown to him; amongst others borrowing from an inspector the smallest pair of hand-cuffs which they had at the police station, and to which there was only one key, which I also requisitioned. These were kept for the use of women, if required : why I procured them will appear later on.

As the clocks were striking the hour for the commencement of the ball, Karl entered my rooms, faultlessly dressed in his evening suit. I was also " in full armour, " because I myself purposed going there latter on.

After we had chatted and smoked for an hour, Karl said, "Well ! shall I go to the ball now ?" I assented, and he quietly lay down on my sofa on his back, folded his arms across his chest ; and, saying, " In ten minutes' time I shall be in the ball-room," closed his eyes, and remained motionless. I watched the clock for ten minutes and then went over to his side. He was in a perfectly cataleptic condition : no pulse to be felt : not the slightest flutter of the heart to be detected by the stethoscope : not a breath dimmed the hand-mirror that I held to his lips. I shook him, spoke to him, but, of course, made no impression; he lay there, to all intents and purposes, dead.

I then prepared to go to the ball myself, and see if he had really carried out his intention : and I knew if I locked the door no one could get in or out, because it was fastened with a Bramah lock. But, "to make assurance doubly sure," I got out the borrowed hand-cuffs and snapped them on his wrists, putting the key in my pocket.

Then I went to the dance, after carefully securing the room door-the windows having a clear forty feet drop. I hurried rapidly the few hundred yards to the Assembly Rooms and went in ; and almost the first person I saw was Karl, solemnly revolving in an old deux-temps waltz, with a lovely girl in his arms.

When the dance was over he took her to a seat, and went to the refreshment counter to get her something-I forget what, now ; I tapped him on the shoulder, and he turned round and said, " Well, you see, I am here, as I told you." He went off to his partner; and I, leaving him with her, shot off at a rapid run to my rooms.

There, on my couch, was still extended the form of Karl ! I again returned to the ball, and there was my friend, promenading with another belle. I remained at the ball enjoying myself, ever and anon coming across Karl, either dancing or flirting ; but I kept a watchful eye on the time. When it was nearly half an hour of the time for Karl to return I went home and sat down to watch the body until the three hours should have expired. I had perfect confidence in my fellow-student's ability, and so waited without anxiety for the denouement.

A few seconds after the three hours had expired, a slight tremor was observable in the eyelids, a long breath was drawn, and then another, and Karl partially sat up. Then his eye fell on the handcuffs, and for the next few moments the air was filled with a series of German expletives and objurgations not to be found in any dictionary.

I went laughingly to unlock them, but I saw that he was really offended. After a pipe, however, he re-covered his usual sunny temper, and discussed the whole process at some length.

A few days after this, Karl proposed to me to exchange bodies for the space of twenty-four hours. I didn't quite see the force of this, having heard of other cases of German students having effected the exchange for a time, and then one of the men had refused to return to his own body, and had permanently occupied his new tenement ; and for this there was no remedy. Therefore I declined point-blank. However, after many days' persuasions, entreaties, and arguments-and reflecting that, after all, it would not destroy the identity of my Ego : I should still have the same mind, the same knowledge, the same soul ; and also, that his was in every way a superior body to mine-I decided to risk it, but for four hours only.

Another thing weighed considerably with me, and that was that it might be some day useful to me to know the modus operandi, not merely in theory but practically. So, one fine summer's day, we soon effected the exchange. *

Yes, I consented to let Karl borrow my body for the short time stipulated : but I should not have done so, in spite of the foregoing reasons, had it not been that I found that the whole happiness of his life was at stake ; and if I did not consent it would be irretrievably ruined. Now, as I have previously stated, I had a very strong affection, almost more than friendship, for Karl ; and, when he confided tome the true state of affairs, I had not the heart to refuse them. Of course, there was a lady in the case.

It appeared that he had been engaged for two years to a very pretty girl who was, in reality, absolutely de-voted to him, but of whom he was insanely jealous. He carried this so far that, if she were only fairly civil to any other man, he accused her of flirting, and was only too ready to believe that every man who paid her the slightest attention was seriously endeavouring to cut him out in her affections. Time after time did the poor girl convince him that his suspicions were unfounded, only for fresh ones to arise the next day with the advent of any stranger.

And it was unfortunate that the girl happened to be the daughter and chief handmaid of the landlord of a hostelry much affected by students, and which was scarcely ever free from the presence of some one or other of these rackety young blades.

Latterly, he had taken it into his head that I-his bosom friend and companion-had designs upon her; and, although both she and I had striven our best to exorcise the demon of jealousy, yet it still lay hiding in his breast.

So, a brilliant thought struck him. He would, at one bold stroke, either convict me of perfidy or else reassure himself completely ; and then, never-no, never- doubt the m�dchen any more.

I gave him credit for candour in telling me that this was the reason why he wanted to borrow my body; and he explained fully his intended course of action.

When duly equipped with my corpus vile, he proposed visiting the fraulein, and-as me- not merely making love to her, but proposing an immediate elopement. If she would have none of my endearments, would not listen to my proposal, he would then know she was his own dear m�dchen. If, on the contrary, she allowed me to kiss and caress her, he would have done with her for ever. It has frequently struck me since that he would have been in an awkward dilemma if she had consented to elope with " me " ; but that by the way.

He said, " Now I shall know for certain how she receives you in my absence."

Well, to be brief, we effected the desired exchange; and I awoke to consciousness to see myself sitting in the arm-chair opposite. For the moment I sat utterly aghast, forgetting the bargain we had made and the transmigration just effected. Then, all at once it flashed across me, and I said, "How do you feel, Karl ?" He rejoined, "My name is Ross; you are Karl ! " Of course, I had forgotten that the name must go with the body. I looked down at myself and saw Karl's monstrous great German feet, ditto hands. I began to feel a little disgusted with myself-that is, my new outward-seeming self. I spoke again, and I had a decided guttural German accent. Then, of course, I got up and looked at myself in the glass over the mantel. I was Karl, sure enough. And there was I (Me) walking- out of the door, humming, " Goodbye, sweetheart, good-bye. " I fancied there was a jeering tone in the voice ; but it might have been imagination.

So there was nothing to be done until Karl returned, but to spend the time in the best manner possible.

I sat down and began to examine myself to see if the physical change had produced a corresponding mental one. So, as Karl was a skilled musician, I sat down with every confidence to the piano to solace myself with music. I boldly struck the instrument, but only a discord resulted ; that was no good.

Wanting a smoke, I felt for my pipe ; but Karl had it out with him in my clothes, so I picked up his great porcelain-bowled German pipe, and filled it with the coarse-cut "kanaster" he invariably smoked to my great disgust. I took a few whiffs, and actually enjoyed it ! Had my tastes, then, become Teutonic as well as my body ? I was destined to prove that they had. Sallying forth, I went to a restaurant for lunch, and the kellner, seeing a typical Deutscher enter, at once placed before me the carte du jour of German viands. Now German cookery had always been an utter abomination to use, and I had sedulously refrained from it. But now I felt a longing for some wurst and sauerkraut. I ate enormously of this, washing it down with sundry backs of lager beer, and wound up with some Limburger cheese. How I luxuriated in these hitherto unspeakably horrible comestibles! being mentally disgusted with myself all the time.

My repast finished, I strolled back to my rooms, and while rummaging my (his) pockets for matches, found the portrait of Karl's fianc�e. I steadfastly looked at it, and began to experience a strong feeling of passionate admiration of the charms there depicted. I no longer wondered at Karl's attachment, for the girl struck in my physical nature the keynote of such an overmastering passion as I had never yet experienced.

In short, I was head over ears in love with her, and a strong determination arose within me to have her for my very own. I forgot all about Karl. I only knew that I loved her; and I seemed to have a consciousness that she loved me, and I revelled in that knowledge.

I was aroused by the church clock chiming the quarters, and then I remembered all, and that in a quarter of an hour more Karl would return.

I was conscious then of possessing two distinct identities there present-not counting my own body, which was absent with Karl. There was my mind-my Ego, my real self-which was not in the least drawn towards the girl ; and furthermore, which strongly remonstrated with my (his) brain for being so attracted, and with my whole body for the overpowering physical longing for her which thrilled its every nerve.

My Ego told me that to gratify my passion, or even to indulge it in the slightest degree, would be treachery to my friend and more than brother ; that even my present feelings were an insult and a wrong to him. The atmosphere of the. place seemed to choke me ; I could scarcely breathe, and again 1 went out into the open air.

There were two ways leading to the inn where Karl's inamorata dwelt, and I knew which way he always went, returning by the same. Presently, almost unconsciously, I found myself on the way to the inn, but by the other road. I asked myself what I was doing there: what was my purpose (having accustomed myself to self-examination) ? I found that I was going there to pass myself off as Karl on the unsuspecting girl, with a purpose as yet undefined, but the very thought of which filled me with a fierce delight, a savage joy that was akin to madness. My Ego said to me, "You are an infernal villain ; the height of treachery could no farther go-black-hearted Judas!" I stopped, appalled, as the sudden sight opened to my mental eye of the fearful depth of the moral abyss into which I was about to plunge.

I turned, and began to retrace my steps, knowing that by that time Karl would have returned and he waiting to resume his body. His body ? Yes !-for the time of air agreement had expired, and if I kept it any longer I should be a thief as well as a villain. I was turning down the street where my lodging was situated, and the temporarily-conquered longing arose with ten-fold force in my heart.

I could stand no more, the physical influence of his body maddening my brain and overpowering the calm, still voice of my Ego. I turned and rushed from the spot; but not home. I went to the inn. [It must he remembered here, not as any excuse, but as some palliation, that I was then only eighteen, and that I had not then become the pupil of the great Magist.]

As I entered the inn door, Lisa ran to meet me, and I showered passionate kisses on her like rain. She said, with some surprise, " What ! back again, Karl ? " We went into the inner room-her chosen place for courting with Karl-and for a full hour I made love to her as Karl.

Then, horror of horrors! " My" voice was heard without asking if " Karl " was here, as he had been seen to come in this direction. I looked through a little peep-hole into the public room, and saw Karl (in my form) looking excessively agitated and uneasy, because he wanted to resume his own proper person again. And, if anything had happened to me, or I had run away, he would never be able to recover it, and Lisa would be lost to him.

I whispered to Lisa, "Go out to him, and tell him you have not seen me; and send him home." She did so, and in that interval of absence, my Ego resumed his mastery. I said to her on her return, " I must go now but promise me something before I go." She promised and I, knowing that Karl would visit her in the evening, after the exchange, said-" I will come again to-night but, for very special reasons, do not then, nor ever after, refer to my coming back again this afternoon and spending this hour with you." 1 made her swear it, and I knew the secret was safe.

Looking back at this distance of time, I can see that I was only actuated by a desire to save them both from utter misery : I had no thought of saving myself, as might naturally be supposed. This is the only bright spot in a thoroughly black business.

[And here, in self-defence, I must make a remark. Had I, in my own proper person, allowed any temptation to lead me to betray my friend, I should have been an unmitigated scoundrel ; and the recollection of such a crime would have clouded and embittered the whole of my after life. But I was Karl! It was not only Karl's body but Karl's brain that yielded-and it was not mine.]

Well, I slowly walked homewards, and found Karl in a fever of anxiety regarding my prolonged absence. We immediately effected the re-exchange of bodies, which I found- somewhat to my surprise--was more easily, and, certainly, more quickly, effected than a change of clothing. My own body felt rather strange to me for a couple of hours, as though it didn't quite fit me ; but that was all.

I asked Karl how Lisa had received him (in my body). He said that he had got her to sit down by him, and then began telling her how he had for a long time entertained a strong love for her. She reproached him bitterly for his treachery to his friend, and absolutely refused to listen to a word. He was perfectly satisfied with her reception of him, and said that he should never doubt her again. He visited her again (as Karl) that night, but she had never referred to the occurrences of the afternoon.

I accompanied him the next day, and, oh !-the irony of circumstances ; she was brimming over with affection to him, while she could barely be civil to me. I was punished with coldness and disdain for crimes of which I was not guilty ; and Karl was receiving redoubled endearments through my sin of the previous afternoon.

Karl and I never exchanged bodies again; one experience of that kind was sufficient for us both. I, however, applied myself for some time to the study of the phenomena of the doppelganger, and derived considerable harmless amusement therefrom. I would walk about the town, meet with a friend, talk to him ; and, suddenly, while in the middle of an interesting conversation would, by an effort of volition, find myself on the couch in my own room. The mystification of my friends was immense.

At this time I met Mr. Price, the proprietor of the largest continental circus, then stationed at Madrid. This gentleman was travelling in search of novelties, and happened to hear of some of my exploits.

He asked me to give him an exhibition of my powers in that line, privately. I did so. The next day he called at my place and asked me if I could do it in his circus. I said that the locale made not the slightest difference. He then said that his idea was to have a trapeze performance, in which I should take part ; and the last act of which should be that I should ascend to the flying trapeze, get it into good swing, and then throw a "somersault off." But instead of catching the other trapeze, or alighting on the ground, as other performers do ; I should, while describing the somersault in mid-air, vanish into space. Could I do that? Of course I could ; because, in reality, I should not appear on the trapeze at all, it would be only my doppel-ganger. There was only one difficulty in the way, and that was, as I could not do a trapeze performance, it followed that neither could my double.

He soon found a way out of that by suggesting that I should only come on for the somersault. So that all that I should have to do would be to climb up the rope, seat myself on the trapeze, swing by my hands, and then throw the somersault. For this performance he would give me �200 for six nights to appear in Madrid.

I accepted his proposal, on the condition that my real name did not appear on the bills, or be allowed to leak out ; and the contract was to be drawn up on his return to Madrid in the following week. Circumstances-Fate, if you will-however, intervened ; and at the time that I should have joined him in Madrid to undergo the preliminary training, I was down with brain fever. It was not to be.

But, enough of " doubles " ; I will turn to pleasanter themes.

When engaged in the Italian War of Independence in 1860, I visited a place called La Cava, a few miles from Salerno. While taking some food in a trattoria, I saw an excited crowd rush past the door, following an old peasant woman, who was evidently flying for her life from as ugly-looking a lot of ruffians-principally lazzaroni-as the whole kingdom of the Two Sicilies could produce. I bolted out into the street, and after the crowd ; and being, after a few months' campaigning, in magnificent wind and condition, soon overtook the fellows. They were shouting mal' occh' ! and Mort' ! (the Neapolitans never by any chance finishing a word), by which they meant " The Evil Eye " and ' Death to her ! '

I congratulated myself on being again in luck, as I had heard a great deal in Southern Italy of the mal' occhio, but had never been fortunate enough hitherto to come across one. So I easily outstripped the crowd, the old woman racing along like a greyhound. As I got within about ten or a dozen yards of her she caught her foot and fell. I then stopped, faced about to the gang of pursuers ; and, drawing my revolver, halted the lot in an instant. Cowards to the backbone, none of them liked to be the six men who would infallibly " lose the number of their mess " from the rapid fire of that unerring barrel, and they did nothing but stand and jabber, while the old woman sat up in the middle of the road glaring at them. At last one of them on the extreme flank, thinking that I did not see him, picked up a sharp stone and hurled it with all its force at the old woman. I turned sharply to see if it had hit her; meaning, in that case, to shoot that fellow-at all events-where he stood.

The stone had missed its aim ; and the old hag (for she looked like a veritable Moenad just then) had sprung to her feet and was standing pointing with a shaking fore-finger at her assailant, and staring straight in his face : her eyes verily seeming to shoot forth fire.

A yell of horror and rage broke from the crowd when the man fell to the ground as though smitten by lightning. Then a reaction set in, and they all bolted back to La Cava at an even quicker rate than they came, shrieking out cries of dismay and terror, and leaving their comrade on the ground. I went up to him-he was not dead, as I at first thought ; but he was helplessly, hopelessly paralysed : it was a case of ''right hemiplegia.'' I dragged him to the side of the road, out of the way of passing vehicles, and went up to the old woman.

I said, " Well, mother, you've punished that scoundrel properly ! " She replied, " Ah ! signor, I could have killed him if I had wanted, but I never take life now." I thought she was a cool old customer, but as I wanted some more information, I offered to see her in safety to her home. She seemed overpowered by gratitude, and consented.

In a short time we arrived at one of the numerous caves in the mountain side, where she said she lived. She added-" All the province know where Matta, the witch of La Cava lives, but they dare not molest me here." I went in and sat down and talked with her. She told me that she lived by telling the fortunes of the country-girls, and selling them charms and philtres to win the affections of their lovers; and I shrewdly suspected that she dabbled a little in poisons; and that, when a jealous husband became too obnoxious, old Matta furnished the means of his removal.

I examined her medicaments and tested her fortune-telling powers ; and found that the first were useless and the second did not exist. But her knowledge of poisons was wide and profound, and her power of "the evil eye " was real.

At last I startled her. I said, " Show me the green ointment !" She did not go pale-her mahogany face could not accomplish that feat-but she trembled violently, and clasping her hands together in supplication, said, " No ! Signor, no ! " However, I soon made her produce it, in a little ancient gallipot about the size of a walnut. I asked her if she made it herself, or who supplied her with it. She acknowledged to the manufacture, and then I quietly told her what she made it from, and how she prepared it. Of course, I simply knew all this from the books of "black magic" I had studied under Lytton. Hermetics have to learn all the practices of "the forbidden art " to enable them to combat and overcome the devilish machinations of its professors. When she found that I knew more than she did, she was in a paroxysm of terror ; and I really believe that she thought she was at last standing face to face with her master-Satan. I put the gallipot, carefully stopped, in my pocket and left her.

I need scarcely say that, in the experiments I subsequently made with it, I never tried it on a human being. But I found that all that was recorded of it was true : that the slightest smear of it on the fifth pair of nerves (above the eyes) gave a fatal power to the glance when so determined by the will ; and, on various occasions, I have killed dogs, cats, and other animals as by an electric shock in this manner.

I think the main inducement which caused me to go to India was the chance of studying the methods of the fakirs. So, to abridge my tale, I will merely say that I had not been long up the country before my khitmutgar announced that a couple of fakirs were waiting in the compound to exhibit before the sahib-log.

My two companions were " old Indians," who had seen these performances repeatedly ; but even they saw something new that day.

The fakirs were told that we would not allow them to perform unless they removed all their clothing except their cummerbunds, wound around them in the manner of bathing-drawers. They consented at once to this, and then went through the usual exhibitions of " the mango-tree growing," and the "basket trick."

The mango seed or orange pip was planted in a flower-pot full of earth, a cloth thrown over it, an incantation muttered, the cloth raised to a height of three or four feet, a luxuriant young tree having been unveiled. It was again covered, and was raised almost instantaneously higher. When the cloth was removed it showed a large shrub covered with blossoms. Again, the process was repeated, and, finally, a tree covered with ripe fruit was shown. The performers gathered and distributed the fruit, which was eaten by the bystanders. Once more the cloth was thrown over the tree. At the word of command it rapidly sank down to the ground. When removed for the last time, there was nothing but a large flower-pot, in which the operator dug his fingers and produces the original seed. They will do this in your own compound, or hard earth or stone, or a chunam pavement hard as granite, or anywhere you like, and as they are perfectly naked, with the exception of a cummerbund (wrapped like a waist cloth and bathing drawers) it is evident that no-thing can be concealed. These are generally travelling " jugglers," as they are called by the British.

Then they did "the basket trick," a wretched imitation of which has been shown in England. They took a little girl of about four years of age, and on a hard ground, placed her under an old hamper or rice basket, scarcely large enough to cover her kneeling down. It was made to do so, however. The child was pressed to the ground by one of the men sitting on it ; the other then began his invocations, and taking the tulwar (sword) as sharp as a razor, thrust it rapidly and furiously through and through the old basket, in every direction, leaving not an inch untouched. The shrieks of the child were fearful, the blood spouted along the blade, the men sitting on the basket seemed to have a difficulty in keeping the child down by reason of her terrible struggles, which gradually grew fainter and fainter, as did her shrieks, until at last all was over. A deadly stillness prevailed, the " juggler " calmly wiped the blood from his sword, and lifted up the basket. There was nothing there. The crowd opened, and the child came running into the circle unharmed. Thousands of English officers and civilians have seen these two feats, and will vouch for them upon their honour. I can procure a lady now living, the daughter of an English missionary, who was operated en in the manner described, to the great terror of her mother who witnessed the performances, and was only prevented from jumping from the flat room of the bungalow into the compound, to save her child through being held fast by the missionary, who had seen the performance frequently, and who knew the child would be unharmed. That lady, like all the other female children whom I have seen put under the basket, and afterwards closely questioned, had not the slightest recollection of the fact ; her father and mother with others can, however, substantiate the circumstance.

After these, one of them asked me to take a rupee from my pocket and hold it tightly in my clenched right hand. I did so, and he-standing at some twenty paces distant-made a series of " passes " in my direction for a few moments, and then appeared to throw something at my outstretched fist. On the instant I felt that, instead of my rupee, something cold and clammy was in my hand. I thought, of course, that it was a small snake, and threw it hastily on the ground. It was a lively frog, perfectly harmless ; and, as we stood looking at it, the fakir advanced and picked it up by one leg. He then opened his mouth and dropped it down his throat. It was seen no more, nor my rupee either; but I reckoned it in afterwards when he held out his brass tray with a plaintive " Bukhshish ! sahib ! "

The next feat was rigging up a kind of tent with cloths and draperies, borrowed from the khansamah, in one angle of the compound. Then they asked us what animals we would like to see come out of the tent. One of my friends suggested a water-buffalo. Instantly one of those useful animals appeared in the tent-opening, came out, and wandered off round a clump of bushes. Next, a royal tiger was selected, and, with a terrific roar, a splendid brute bounded out nearly to our feet, then turned and went after the buffalo. My turn came then, and I was determined to select an animal that I knew neither of the fakirs had ever seen, thinking that that would test their power to the utmost, if not prove an impossibility. So I said, "a kangaroo." I could not make them understand what kind of an animal it was-at which I secretly rejoiced, and at once said, "Never mind what it is like, produce it." They rejoined, "Will the Sahib log know him when they see him ?" "Oh, yes !" we all said, "trot him out ! "--and, at the word "Hitherow ! " a fine "old man" kangaroo hopped out, took a flying leap over the bushes, and disappeared. I hope he didn't fall in with that hungry-looking Bengal tiger.

Next, the thin fakir took a tulwar of a straighter patterned blade than those usually met with ; and placing its point to the right side of the stouter one, quietly and deliberately ran it through his abdomen until at least three inches of the point protruded at the left side. There was no blood to be seen, and the man walked round for us to inspect the genuineness of the transfixion. We wanted to pull it out, but he would let no one but his comrade touch it. When withdrawn we carefully examined the sword, and saw that it was a teal weapon-no spring business.

Various other minor feats were shown, and then came the piece de resistance. Borrowing a long cord, which was brought by one of the syces, the thin man threw one end up in the air to its full stretch-about 39 feet, more or less.

It appeared to catch on to some invisible support, and hung down straight ; and the fakir invited us to pull at it and test it, which we accordingly did. He then began climbing up the rope until he arrived at the top, where he calmly seated himself on air, and commenced pulling it up. When he had completely done this, his companion called out, " 'Jaldi jao ! " (Go quickly !), and, while we looked at him, he vanished.

We naturally expected to see him come walking up to us afterwards from behind the bushes, or elsewhere. Bat no : his comrade collected the " bukhshish," and, with many salaams, departed to join him elsewhere.

My next reminiscence is an experience at Simla. I had made the acquaintance of many fakirs, and had examined their feats and probed their mysteries ; but I heard of one man to whom common report attributed all the powers of Moses-and more. This was a native jeweller and diamond merchant at Simla, a man of immense wealth, highly educated and polished. I determined to go to Simla, in the hills, and interview him.

I knew a man who had been sent up there to recover after an attack of enteric fever, a captain of Bengal Lancers, and I prepared to visit him. In brief I did so, and arrived at the bungalow, jointly occupied by my friend and a Scotch surgeon-major of Ghoorkhas, just before sunset. During the evening, over our cheroots and brandy-pawnee. I asked if they knew Mr. Jacob. " Rather ! who didn't, at Simla ? "

I expressed my intention of making his acquaintance, but my friend said that he did not think I should manage it in the few days I had at disposal. The surgeon-major said, relapsing into broad Scotch in his excitement, "Dinna go, laddie ; he's na canny." I said that uncanny or not, I had come on purpose ; and, being an obstinate Yorkshireman, I meant to carry it through.

The next morning I went to Mr. Jacob's bungalow, higher up, about three-quarters of a mile from where I was staying. His bearer informed me that he was away, and was not expected home for three days, when he had invited three gentlemen to tiffin. I left my card aid promised to call again, as I was obliged to leave Simla the day after his expected return ; and I left word that I had come some hundreds of miles to see him.

To strengthen my chances, I marked in pencil a hieroglyphic on the card ; not knowing to what school he belonged, except that he was not a Hermetic. Had he been so, no single word about him would have appeared in these pages from my pen. I thought it just possible that he might recognise and know the meaning of the hieroglyph.

The result exceeded my wildest expectations. Three days afterwards, 1 returned from an early morning ride to find that Mr. Jacob had himself called at our bungalow, and left his card for me, with the hope that I would join his party at tiffin that day. My Scotch friend looked very glum, and was sure some harm would come of it.

However, at the appointed time, I gaily mounted the captain's tat, and set forth. When I arrived, the other three guests were there-one of them, a general officer whose name is a household word in England and India. I was received with great empressement by Mr. Jacob (thanks to the hieroglyph), and we proceeded to enjoy the repast.

Afterwards, when the Trichinopolis were lighted and desultory conversation set in, our host was asked by the General to show us some, what he called "tricks." I could see that Jacob didn't like the word ; but he simply said, " Yes, I will show you a trick." Then he told a servant to bring in all the sahibs' walking-sticks. Selecting one, a thick grapevine stick with a silver band, he said, " Whose is this ? It was claimed by the General, and a glass bowl of water, similar to those in which gold-fish are kept, was placed on the table. Mr. Jacob then simply stood the stick on its knob in the water and held it upright for a few moments. Then we saw scores of shoots like rootlets issuing from the knob till they filled the bowl and held the stick upright; Jacob standing over it muttering all the time. In a few moments more a continuous crackling sound was heard, and shoots, young twigs, began rapidly putting forth from the upper part of the stick. These grew and grew ; they became clothed with leaves, and flowered before our eyes. The flowers became changed to small bunches of grapes ; and, in ten minutes from the commencement, a fine, healthy standard vine loaded with bunches of ripe black Hamburgs stood before us. A. servant carried it round, and we all helped ourselves to the fruit.

It struck me at the time that this might only be some (to me new) form of hypnotic delusion. So, while eating my bunch, I carefully transferred half of it to my pocket, to see if the grapes would be there the next day.

When the tree was replaced or, the table Jacob ordered it to be covered with a sheet ; and, in a few minutes, there was nothing there but the General's stick, apparently none the worse for its vicissitudes.

I then described the performances of different fakirs whom I had seen, especially the only one which puzzled me-the transfixion of the body with a tulwar. Mr. Jacob smiled and said, "Oh, that's nothing. Stand up." I did so, and he, taking down a superbly mounted and damascened yataghan from Persia, which formed part of a trophy of arms on the wall, drew it from its scabbard and held the point to my breast, saying only "Shall I?" I had absolute confidence in him, so simply said "Certainly." He dropped the point to about two inches below the sternum (breast-bone) and pushed slowly but forcibly. I distinctly felt the passage of the blade, but it was entirely painless, though I experienced a curious icy feeling, as though I had drunk some very cold water. The point came out of my back and penetrated into the wood panelling behind, which, if I remember rightly, was of cedar wood. He left no of the weapon and laughingly remarked that I looked like a butterfly pinned on a cork. Several jokes at my expense were made by the others ; and, after a minute or two, he released me. I looked rather ruefully at the slit the broad blade had made in my clothes, but Jacob said, "Never mind them ; they'll be all right by-and-bye." He began to show us another wonder, and I forgot all about it. But about an hour afterward there was no trace whatever of any damage to the clothes.

Presently he said, " Well, gentlemen, I hope I have amused you. I want you now to amuse me by each giving me an account of some battle he was in (especially an occasion of being wounded). I am intensely fond of tales of war and heroism." Well, we had all four of us plenty of experiences of that sort, but in the Service it is " bad form " to talk about one's own doings, so that he had considerable difficulty in getting anyone, to begin. At last the General opened the ball by giving (at our special request) an account of the Balaklava ride, in which he had taken part.

He told it as a brave soldier would, simply, but earnestly, and manfully. Our host watched him narrowly, and listened like one entranced, not missing a single word. He then took from the inner pocket of his jacket a small baguette, and waved it towards the inlaid panelling of the room.

In an instant a thick mist gathered there, of a deep violet hue, which rolled away to each side, and there was plainly visible to our eyes the field of Balaklava with the Light Brigade drawn up. We saw Nolan ride up, we heard the trumpets blare out the advance, and, finally, the "charge." We watched the death of that unfortunate officer, and then saw the Light Brigade in their headlong charge on the guns. Every incident repeated itself before us. We saw them spike the guns and return, but the most distinct figure to our eyes was that of our friend the General. We saw their return impeded by a dense mass of Russian lancers, two of whom speared the General (he was not a general then) while he was cutting Clown a third on his right front. Down he went, and the shock of battle rolled on, leaving him on the ground in our full view. Presently he staggered to his legs and caught a riderless troop-horse, which came up to him without any shyness when be whistled a call. We saw him mount with extreme difficulty and ride off to the British lines, where he arrived in safety, though shot and shell hurtled round him at times like a hail-storm.

Another wave of the baguette, and all disappeared ; and there was nothing but the pattern of the inlaid wood to leek at. We looked at one another and drew a long breath, the General saying only, " Well ! I'm blanked !" In those days cavalrymen used more forcible expletives than is the custom now. We took fresh cheroots, and once more composed ourselves to hear the experiences of the others. To these we naturally listened with a heightened interest, knowing that at the conclusion of each story we should see the actual incidents reproduced before our eyes.

We did, and we saw more than we heard ; because one officer, in relating the share he took in the assault on the Alumbagh, entirely omitted to mention a feat of brilliant daring which he performed on that occasion, in engaging single-handed in a furious hand-to-hand conflict with two gigantic sepoys-he was only a little fellow. Anyhow, we saw him kill them both with his own blade (his revolver was empty, and no time to re-load). When we " chaffed " him after about omitting this detail, he only said, " Well, of course I didn't want to gas."

When all our stories and their ensuing visions were concluded, we discussed what we had seen, and one or two of the guests were sufficiently ill-advised to ask Mr. Jacob how such a thing as the actual reproduction of an event which had occurred some years before was possible. He told them that every event that had ever taken place in the history of the world was actually still existing in the astral light, and could be reproduced at any time and place by those who possessed the know-ledge and the power. In fact, that so to speak, as words spoken into a phonograph by people since dead, still existed, and could be reproduced at will: so that all actions and events were for ever in existence.

I told him that this agreed in toto with the teachings of the Hermetics ; and also pointed out that the New Testament stated that one day all the deeds that had been done should be made manifest, whether they were good or evil. All he said was, " No difficulty about doing that! "

Presently he asked us if we would like to look at his gardens (a most unusual proposition there). We consented out of politeness, and went outside. We found there an artificial lake or large pond, of which we took no particular notice, and lounged about in the shade chatting and smoking. Presently, the officer to whom Jacob was talking at some little distance from the rest, called out: "Mr. Jacob is going to walk on the water." Jacob said, " Why not ? ' and immediately stepped not into but on the water, and deliberately walked right across the pond. The water being very translucent, we could see the astonished fish darting away in all directions from under his feet. When he got to the other side he turned round and came back again. As he stepped on the ground I requested to look at his shoes, to see if they were wetted at all. The soles appeared just as if he had walked over a wet pavement, and that was all. He said : " That is nothing; anyone who can float in air" (Angelice levitate) "can walk on water ; but I will show you something that really requires power."

It was a baking hot day in the hot season, and although considerably cooler up there in the hills than in the plains, it was still as ardent as a hot summer's day in England.

Bringing out the baguette again, he waved it slowly round his head. Presently the air was full of butterflies. They came by thousands, by millions, till they were as thick in the air as a heavy snowstorm. They settled on everything, on us, on our hats, our shoulders, anywhere, like bees swarming, till we presented a ridiculous spectacle. The scene was so ludicrous that we burst into roars of laughter. This seemed to offend Jacob, who was rather touchy on some points, so he said, " Ali ! you laugh ; we will have no more of it." The butterflies rose from where they had lit, rapidly went up into the air, higher and higher, till they formed a dark cloud passing the sun, and then drifted off out of sight altogether.

We went into the bungalow again, but there was a decided coolness perceptible in our host's manner, and I, for one, was not sorry to prepare to leave.

Before we broke up, however, Mr. Jacob requested a few words privately with me. I followed him out to the verandah, and we spoke on occult subjects for a few minutes, and then he said to me. "I will give you a special experience, which will give you something to think about." Just what I wanted !

He said, "Shut your eyes and imagine that you are in your bedroom in your bungalow." I did so. He said, "Now open your eyes." I opened them to find that I was in my bedroom- throe-quarters of a mile in two seconds! He said, Now shut them again, and we will rejoin our friends." But I wouldn't have that at any price ; because the idea of hypnotic delusion was still present to my mind ; and, if it were so, I wanted to see how he would get over the dilemma.

He did not try to persuade me, but only laughed, saying, " Well if you will not, then good-bye," and he was gone. I instantly looked at my watch, as I had done in his verandah at the commencement of the experiment, and two minutes had barely elapsed.

I walked straight out of my bedroom to the dining-room where both my friends were sitting. They stared and wanted to know " How the deuce I got there " So I sat down and told them all that occurred. The doctor said, " Let us see the grapes." I felt in my pocket and they were there all right, and passed them to him. He turned them over very suspiciously, smelt of them, and finally tasted one. " They're the real thing, my boy; genuine English black Hamburgs," he said, and proceeded to devour the lot. Then the captain said, " But where's the tat ? " I replied that I had forgotten all about it ; I supposed that he had better send for it. Calling a servant, he told him to go to the stables and send a syce up to Sahib Jacob's bungalow for the tat. In a few minutes the bearer returned with the syce, who said that the tat was at that moment safe in his own stable. We stared at one another, and then went to see for ourselves. Sure enough he was there.

To those who are specially interested in occultism, I may say that Mr. Jacob is not actually a Yogi ; though he has studied Yoga, and by its means performed the feats here recorded. The baguette he employed was almost identical with that of the Hermetists.

My next experience relates to those much-maligned individuals-the " rain-makers" in Africa. It is the custom for missionaries, and people who have never seen them at work, to ridicule the idea of their possessing the powers which they claim. But their power is a very real one ; and the argument that they only commence operations when they can tell that rain is coming is absurd on the face of it.

The kings and savage chiefs of \Vest and South Africa are skilled observers of the weather, and know quite as much about it as the rain-makers. And it must be remembered that they never send for these men until every chance is hopeless ; and, further, that the lives of the rain-makers are always staked on their success. Failure means death-death on the spot- accompanied by torture of the most horrible kinds.

I was on a visit to one of the petty " kings " in what is today called the Hinterland of the Cameroons (now a German settlement), and it was of great importance to me to keep the king in good humour, as his temper, never very good, was getting absolutely fiendish by reason of the long drought which had prevailed. There had been no rain for weeks, all the greener vegetables had perished, and even the mealies were beginning to droop for want of water, and the cattle in the king's kraal died by scores. Celebrated rain-makers had been sent for, but so far none had turned up.

One day, the hottest 1 ever saw in Africa or anywhere else, I was taking my noonday siesta when the thunderous tones of the big war-drum filled the air. Like everyone else, I sprang to my feet and rushed to the king's kraal, wondering what new calamity was going to befall me. All the warriors assembled, fully armed, in the space of a few minutes, speculating, what the summons boded--war, human sacrifices, or what ? But their anxious looks were turned to joy, and a deafening roar of jubilation went up when the king came out followed by two rain-makers; who had arrived a few minutes before.

The longest day that I live I shall never forget that spectacle. A ring of nearly three thousand naked and savage warriors, bedizened with all their finery of neck-laces, bracelets, bangles, and plumes of feathers; and armed with broad-bladed, cruel-looking spears, and a variety of other weapons ; the king seated, with his body-guard and executioners behind him ; in the middle two men, calm, cool, and confident ; and above all the awful sun, hanging like a globe of blazing copper in the cloudless sky, merciless and pitiless.

I can see those two men now, as if it were but yesterday -one an old man, a stunted but sturdy fellow with bow-legs ; the other, about thirty, a magnificent specimen of humanity (if I remember rightly he was a Soosoo), six feet in height, straight as a dart, and with the torso of a Greek wrestler, but a most villainous face.

They began their incantations by walking round in a small circle singing some wild barbaric chant, and ever and anon throwing up into the air a fine light-coloured powder, which they kept taking from pouches slung at their sides. This went on for about twenty minutes or more, and was just beginning to grow insufferably tedious (the crowd all this time standing motionless and silent, like so many images carved in ebony) ; when, suddenly, the old man fell down in convulsions. I was within ten yards of him, and watched him most carefully, and (speaking as a medical man), if ever I saw a genuine epileptic fit, I saw one then. As he rolled on the ground in horrible contortions, foaming at the mouth like a mad dog, his comrade took not the slightest notice of him, but stood like a stone statue pointing with his outstretched arm to a point in the zenith slightly to the westward, his glaring eyeballs being turned in the same direction. All eyes were turned to follow his gaze, but nothing was visible.

But stay! Is that a darker shade coming over the intense blue of the sky at that point ? It is-it deepens to purple-then heavy clouds appear, apparently from nowhere ; and, before a whole minute has expired, the sun has gone, and vast clouds of inky blackness cover all the face of the heavens.

Still motionless stands the statue. Blacker and more black grows the pitchy darkness, until it becomes almost impossible to see. But still that ebony figure stands silently pointing. Then the lowering vault of heaven is riven by a lightning shaft, that seems to blind one by its awful glare: a peal of thunder accompanies it that sounds like the " crack of doom " ; and then down comes the rain in torrents-in waterspouts, tons and tons of it. Verily, they earned their reward !

Of the feast that followed, when the rain had abated into a steady, business-like downpour that never ceased for two whole days and fairly transformed the parched and thirsty land, I will not speak. It was like all other royal feasts in West Africa.

After it was over I visited the rain-makers, who were fortunately allotted the next hut to mine. I found that they both spoke Soosoo and a little Arabic (which last they had picked up from the Arab slave-dealers of the interior), so we got on finely.

By certain means, known to all occultists, I at once acquired their confidence, and they agreed to show me what they could do. There was a fire on the ground in the centre of the hut, and we seated ourselves around it, at the three angles of an imaginary triangle.

Throwing some dried herbs and mineral powders (all of which I carefully examined and identified) into the fire, they commenced singing and rocking themselves backward and forward.

This continued for a few minutes, when, all rising to our feet but keeping the same relative positions, the old man began making a series of motions, like mesmeric passes, over the fire. Almost instantly the fire seemed alive with snakes, which crawled out of the fire in scores, and in which I recognised the most deadly serpent on the face of the earth-the African tic-polonga. These brutes raced madly round and round the fire, some endeavouring to stand on their tails, hissing loudly all the time, until it absolutely produced the effect on the spectator of a weird dance of serpents. On the utterance of one Arabic monosyllabic word, the polongas hurled themselves into the fire and disappeared.

The younger man, who had hitherto taken no active part, then opened his mouth wide, and a snake's headpopped out. He seized hold of it by the neck, and pulled out of his throat a tic-polonga between two and three feet long, and threw it also in the fire. I said, "Do it again," and he repeated the feat several times.

It must be remembered that both men were entirely naked at this time, excepting for their feather Lead-dresses, so no clever jugglery or sleight of hand was possible.

The next thing was that the old man lay down on the floor, and told us to take him by the head and the heels and raise him up. This we did to the height of about three feet from the floor, he having made himself perfectly rigid. We held him there for a moment, and then he softly " floated " out of our hands and sailed right round the hut, I following him closely. He then approached the wall, feet first, and fairly floated through it into the outside darkness. I immediately felt of the spot where he had gone through, expecting to find a hole ; but no, all was as solid as stout beams of timber and a foot of sun-baked clay could make it. I rushed outside to look for him, and even ran round the hut ; but, what with the dark night and the heavy rain, I could see nothing of him. So I returned, wet to the skin. The other man sat by the fire alone, singing.

In a few moments the old man came floating in again, and sat down at his point of the triangle. But I noticed that the feathers in his head-dress were dripping wet, and that his black skin fairly glistened with rain.

The last incident was to be an evocation. Other substances and odoriferous gums being thrown into the fire, we stood in solemn silence, although I could see by the continuous rapid movements of the old man's lips, that he was silently repeating the necessary formula. After a long time, that seemed an hour, the figure of a venerable old man slowly arose in the centre of the fire, in puribus nataralibus. He was evidently an Englishman (having. I noticed, along purple cicatrix on his back), but I could not get a single word out of him, although I tried several times. The old rain-maker shook like a leaf, and was evidently almost frightened out of his wits. He could only gasp and stare at the Englishman. At last he managed to mumble out the two words necessary to dismiss him, and, as I looked, he was gone.

Neither of the rain-makers seemed to know who, he was, and kept up such a rapid gabble to each other for a long time after he had gone that I could not properly follow them ; but a few words gathered here and there showed me that they were thoroughly terrified. The Englishman was not at all what they had expected to see. What they looked for was a black.

I could get neither sense nor reason out of them any more that night, so left them and went to my own hut for a good sleep. When I visited them the next evening, just after sunset, they were quite willing to resume the s�ance. This time we formed an isosceles triangle, instead of an equilateral, I occupying the apex. They were very particular on both occasions in getting the exact distances they required.

I sat, therefore, at the apex and they stood at the two other angles. Then the old man began reciting in a loud voice, the other occasionally joining in at regular rhythmic intervals. Presently, as I looked, I saw the old man gradually growing taller and taller until he was level with the 6-feet Soosoo. Then they both begun to slowly shoot upwards till their heads touched the roof of the hut, about 9 ft. Still keeping on the recitation, they decreased in height minute by minute, till a couple of mannikins, not more than two feet in height, stood before me. They looked very repulsive, but horribly grotesque. Then they gradually resumed their natural height ; and, for the first and last time of my acquaintance with them, they both burst out into a genuine, hearty, unsophisticated peal of laughter.

But this was only for a moment; for the next was to be a more serious performance--a reproduction of one of the far-famed mysteries of Baal, when his priests danced before his altar and gashed themselves with knives.

For this performance I had to remove from my position at the apex of the triangle and stand out of the way against the wall of the hut. The two performers began by slowly walking round the fire in as wide a circle as the space would permit ; and every now and then, revolving on their own axes, singing a dirge-like chant. Presently they quickened the time, both of their singing and movement-discontinuing the walking altogether, and progressing round the circle solely by spinning like tops-the two men going in opposite directions. Round and round they went, fiercely gyrating and shouting their song louder and louder, until it ended in a series of car-splitting shrieks. Then suddenly, in each man's hand appeared a glittering knife with which, every time they passed each other-twice in each circle-they gashed their naked flesh in the breast, arm face, and sides.

The scene now became one of sickening horror-the whirling black figures, streaming with blood; the ear-splitting yells in that confined space ; the glaring eye-balls and demoniac expression of their faces; and, above all, the horrible smell of the flowing negro blood seemed like a terrific nightmare or a scene in Pandemonium. I have pretty strong nerves, but I found the strain on them intense ; and I was truly glad when the old man suddenly stopped his gyrations and calmly sat down by the side of the hut, as this evidently foretold a speedy close to the horrible scene.

The old man took no notice of his gaping wounds, but kept his eyes fixed on every movement of the younger one, who had now ceased yelling and slashing himself, hut kept on spinning round and round, slowly and more slowly, till at last he fell prone and utterly exhausted.

The elder then picked up both knives (which had short, trowel-like blades, ground to a razor edge on both sides), wiped them, and carefully smeared both sides of the blades with some horrible unguent. While he was doing this, I was carefully examining the wounds of the other man, and found them perfectly satisfactory, going through skin and muscle, and bleeding profusely ; though I could not detect in any case that an artery had been cut; it was distinctly venous blood that issued from the wounds.

The old man then took the " doctored " knife of the younger one and carefully stroked every cut with the blade, beginning front the head, and stroking in a down-ward direction. I could scarcely believe my eyes when, under this treatment, the gaping edges of the wounds Immediately closed, and the blood ceased to flow. He then took some more of the grease on the palms of his hands, and vigorously rubbed the young man all over the trunk for a few minutes. Here I may remark that all the wounds were "above the belt." When his operations were completed, he was standing in a large pool of blood which had run down from his own wounds, but he still took no notice of them.

The young man then performed precisely the same operations on the elder; and then both came and stood in front of me for examination. I made a good blaze in the fire, and then overhauled them minutely; but there was no trace of a single scratch to be found-not even a scar!

I had seen enough for the time being, and was glad to get out into the pure air, with the promise to visit them again the next day. I went the next evening, but the hut was empty : they had gone away at daybreak-no man knew whither. When I asked the king where they had gone: for all answer he pointed to the setting sun. It was dangerous to persevere, and I said no more. I never saw them again.

The psychological and psychical portions of Rider Haggard's "She " strike me as being not so much the creation of a vivid imagination as the simple recital-or, perhaps, one should say, the skilful adaptation-of facts well known to those who penetrated the recesses of the west coast of Africa a generation ago. Astounding, terrifying, and incredible as the powers of Ayesha appear to the casual reader, yet to the men who laboriously threaded the jungle and haunts of the riverain portion of West Africa, long before Stanley was thought of, they only seem like a well-known and familiar tale. The awful mysteries of Obeeyah (Vulgo Obi) and the powers possessed by the Obeeyah women of those days, were sufficiently known to all the slave traders of the West Coast to make the wonders worked by " She " seem tame by comparison. And always excepting the idea of the revivifying and rejuvenating flame in the bowels of the earth in which "She" bathed, there is nothing but what any Obeeyah woman was in the habit of doing every day. And, the fact forces itself upon me that " She " is neither more nor less than a weak water-coloured sketch of an Obeeyah woman, made white, beautiful and young, instead of being, as she invariably is, or was, black, old, and hideous as a mummy of a monkey. This is not only my own opinion, but that of all the old comrades of "the coast" of thirty years ago, to whom the subject has been mentioned. Although, the Obeeyah men were, without exception, clumsy and ignorant charlatans, and simply worshipped Mumbo Jumbo, the Obeeyah women were of a different creed: offered human sacrifices, under the most awful conditions, to Satan himself, whom they believed to inhabit the body of a hideous man-eating spider; practised evocation of evil spirits; and, beyond all dispute possessed powers far exceeding anything ever yet imagined in the wildest pages of fiction. To even hint at some of these wonders would be to subject one to one of three alternatives-to be considered either Menteur, Farceur, or Fou.

There is nothing on record in the ancient myths of any religion that is not done by the Obeeyah of to-day. The human imagination-whatever philosophers may think-has not the power to create ; and, whatever you have read of magical powers-especially those of necro-mancy--are absolutely possible ; absolutely true ; absolutely accomplished ! From Moses to Bulwer Lytton ; from Jannes and Jambres of Egyptians, to all the wonders of India, there is nothing-never has been anything-that cannot be done by the African Obeeyah.

I remember more than thirty years ago meeting an Obeeyah woman some hundreds of miles up the Cameroons river, and who had her residence in the caverns at the feet of the Cameroons mountains. In parenthesis, I may remark that I could not have existed there for one moment had I not been connected in some form or other with the slave trade. That, by the way. Judge for yourselves, whether "She" was not " evolved" from Sub�, the wellknown Obeeyah woman of the Cameroons, or from one of a similar type. Sub� stood close on six foot, and was supposed by the natives to be many hundred years of age ; erect as a dart, and with a stately walk, she yet looked two thousand years old. Her wrinkled, mummyfied, gorilla-like face, full of all iniquity, hate, and uncleanness, moral and physical--might have existed since the Creation, while her superb form and full limbs might have been those of a woman of twenty-four. " Pride in her port, and demon in her eye " were her chief characteristics ; while her dress was very simple, consisting of a head dress made of sharks' teeth, brass bosses, and tails of some species of lynx. Across her bare bosom was a wide scarf or baldrick made of scarlet cloth, on which were fastened four rows of what appeared like large Roman pearls, of the size of a large walnut. These apparent pearls, how-ever, were actually human intestines, bleached to a pearly whiteness, inflated, and constricted at short intervals so as to make a series of little bladders. On the top of her head appeared the head of a large spotted serpent-presumably some kind of a boa constrictor-the cured skin of which hung down her back nearly to the ground. Round her neck she wore a solid brass quoit of some four pounds weight, too small to pass over her head, but which had no perceptible joint or place of union. Heavy bangles on wrists and ankles reminded one somewhat of the Hindu woman's, but hers were heavier, and were evidently formed from the thick brass rods used in "the coast trade," and hammered together in situ. Her skirt was simply a fringe of pendent tails of some animal-presumably the mountain lynx-intermingled with goats' tails. In her hand she carried what seemed to be the chief instrument of her power, and what we in Europe should call " a magic wand." But this was no wand, it was simply a hollow tube about four inches long, closed at one end and appearing to be made of a highly glittering kind of half ivory. Closer inspection, however, showed that it was some kind of reed about an inch in diameter, and incrusted with human molar teeth, in a splendid state of preservation, and set with the crown outwards. When not borne in the right hand this instrument was carried in a side pouch or case leaving the open end out.

Strange to say-this mystery I never could fathom -there was always a faint blue smoke proceeding from the mouth of this tube, like the smoke of a cigarette, though it was perfectly cold and apparently empty. I shall never forget the first day on which I asked her to give me a specimen of her powers. I quietly settled down to enjoy the performance without expecting to be astonished, but only amused. I was astonished, though, to find this six feet of humanity weighing at least eleven stone, standing on my outstretched hand when I opened my eyes (previously closed by her command), and when I could feel not the slightest weight thereon. I was still more so when, still standing on my outstretched palm, she told me to shut my eyes again and reopen them instantaneously. I did so, and she was gone. But that was not all ; while I looked round for her a stone fell near me, and looking upwards I saw her calmly standing on the top of a cliff nearly five hundred feet in height. I naturally thought it was a "double "-that is, another woman dressed likelier, and said so to the bystanding natives, who shouted something in the Ephic language to her. Without much ado, she walked-not jumped-over the side of the cliff, and with a gentle motion, as though suspended by Mr. Baldwin's parachute, gradually dropped downwards until she alighted at my feet. My idea always was that this tube of hers was charged with some-to us-unknown fluid or gas, which controlled the forces of nature ; she seemed powerless without it.

Further, none of her "miracles " was, strictly speaking, non-natural. That is, she seemed able to control natural forces in most astounding ways, even to suspend and overcome them, as in the previous instance of the suspension of the laws of gravitation : but in no case could she violate them. For instance, although she could take an arm, lopped off by a blow of her cutlass, and, holding it to the stump, pretend to mutter some gibberish while she carefully passed her reed round the place of union (in a second of time complete union was effected without a trace of previous injury), yet, when I challenged her to make an arm sprout from the stump of our quartermaster, who had lost his left fore-arm in action some years before, she was unable to do so, and candidly declared her inability. She said, " It is dead ; I have no power "-and over nothing dead had she any power: After seeing her changing toads into ticpolongas (the most deadly serpent on the Coast) I told her to change a stone into a trade dollar. But no, the answer was the same-" It was dead."

Her power over life was striking, instantaneous, terrible ; the incident in " She " of the three blanched finger-marks on the hair of the girl who loved Callikrates and the manner of her death, would have been child's play to Sub�. When she pointed her little reed at a powerful warrior in my presence-a man of vast thews and sinews-with a bitter hissing curse, he simply faded away.

The muscles began to shrink visibly, within three minutes space he was actually an almost fleshless skeleton. Again, in her towering rage against a woman, the same action was followed by instantaneous results, but instead of withering, the woman absolutely petrified there and then. Standing erect, motionless, her whole body actually froze as find as stone, as we see the car-cases of beasts in Canada. A blow from my revolver on the hand, and afterwards all over the body, rang as if 1 were striking marble. Until I saw this actually done, I must confess that I never really believed in Lot's wife being turned into a pillar of rock salt. After it I was disposed to believe a good deal.

One of the things which most impressed me was that she poured water from a calabash into a little paraffin, scooped by her hands in the soft earth, but this was nothing but water, I satisfied myself by the taste. Telling me to kneel down and gaze steadfastly on the surface of the water, she told me to call any person whom I might wish to see, and here a rather curious point arose. She insisted upon having the name first. I gave her the name of a relative Lewis, which she repeated after me three times to get it fixed correctly on her memory. In repeating her incantation, a few minutes afterwards, she pronounced the word " Louise," though I did not pay much attention to it at the time. When, however, her wand waved over the water, evolving clouds of luminous smoke, I saw distinctly reflected in it, after those clouds had passed away, the face and form of a relative of mine standing in front of the audience, evidently reciting some composition. I told her that she had made a mistake. I did not acknowledge to hate seen anything for some time. At last I told her that it was the wrong person; then, naturally, argument followed. She insisted that I said Louise. However, at last I taught her the correct pronunciation of Lewis, and I saw the man I wanted sitting with his feet elevated above his head, more Americana, and calmly puffing his pipe while reading the letter. I need scarcely say that I verified the time at which these things occurred, and in both instances I found then, allowing for the difference in longitude, absolutely and exactly correct.

Space will not allow, or I could go on for hours relating the wonders that I have seen Sub� perform. The most wonderful of all I have left untold, because they seem even to myself utterly incredible, yet they are there, buried into my brain, ever since that awful night, when I was a concealed and unsuspecting witness of the awful rites and mysteries of the Obeeyah in the caverns of the Cameroons.

The very root and essence of Obeeyahism is devil worship, i.e., the use of rights, ceremonies, adjurations, and hymns to some powerful and personal spirit of evil, whose favour is obtained by means of orgies, which for horror and blasphemy and obscenity cannot have been exceeded-if, indeed, they have ever been equalled-in the history of the world. These things are too utterly horrible even to be hinted at.

The term obeeyah (vulg. obi; pronounced obee), conveys a truer idea of the sound of the word than obi, because always after the pronunciation of the last syllable there is the African pant or grunt, which I have roughly endeavoured to reproduce by the syllable yah, O-bee-yah. One curious fact in connection with the Obeeyahism, and which seems almost to link it with bygone ages as a remnant of the old serpent worship, is what we read in Mosaic Scriptures about the Witch of Endor. The Hebrew phrase, thus freely rendered by the translators, literally means one who asks or consults O-B, not Oh, but O-B, or two letters signifying " a serpent." Now the Obeeyah women always wore a serpent on the head, and some of them would even have a live one twisted round their necks.